Impacting policy with evidence-based research: 5 open access STEM papers

By Leah Kinthaert, July 2023

Kim Dumont opens her piece, Reframing Evidence-Based Policy to Align with the Evidence, with an excellent explanation of research impact: "A central tenet of evidence-based policy is that society will be better off when research is used."

The assumption is, that when policies are based on scientific evidence, they will be correct, and therefore effective in their goals. And a new study shows that evidence-based policy is also more likely to be enacted into law.

In their article, To Support Evidence-Based Policymaking, Bring Researchers and Policymakers Together, D. Max Crowley and J. Taylor Scott report that "a review of federal behavioral health legislation over the last 30 years found that bills that explicitly referenced scientific evidence were over three times more likely to be enacted into law than bills that did not. We found similar results in other federal policy areas, such as substance abuse and human trafficking."

It is clear that, with evidence-based research in their hands, policymakers are directly empowered to make change.

At Taylor & Francis, we're committed to helping our authors maximize their research impact. We did a deep dive into data from Altmetric, which monitors the reach of research through online interactions. We are proud to say that, in the past three years, we found over 1,000 examples of our open access research being utilized in policy documents. We then honed in on STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering, and Math), and there were over 280.

What follows is a look at five Taylor & Francis open access research articles specifically in STEM topics published in the past three years, that directly influenced recent policy documents from some of the largest and most influential organizations in the world. These include the World Health Organization (WHO), U.K. Parliament, The Publications Office of the European Union, the World Bank, and the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO).

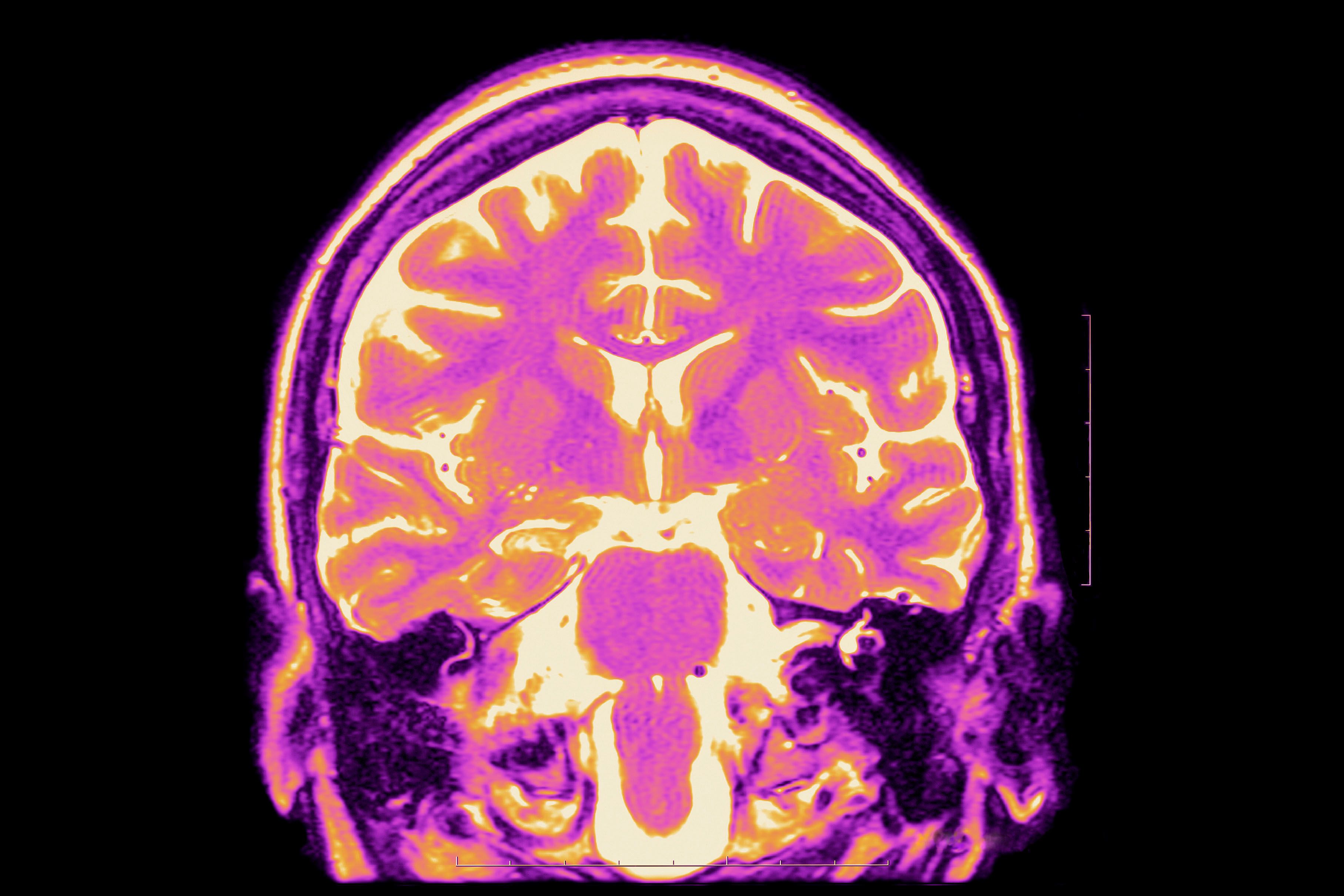

Improving the global diagnosis and treatment of epilepsy

The World Health Organization (WHO) tells us that 50 million people globally have epilepsy.

Their 2022 technical brief "Improving the lives of people with epilepsy" describes the actions needed to do just that, and implement the approach of "The Intersectoral global action plan on epilepsy and other neurological disorders (2022-2031)," adopted in 2022 by the World Health Assembly.

Citing several research studies including the open access paper "Dramatic outcomes in epilepsy: depression, suicide, injuries, and mortality" from the journal Current Medical Research and Opinion, WHO gives the startling statistic that "the risk of premature death for people with epilepsy is estimated to be three times that of the general population, but this risk may be up to seven times higher in some low-resource settings."

The WHO brief continues: "Up to 70% of people with epilepsy could become seizure-free after appropriate diagnosis and antiseizure medicines, which can cost as little as US$ 5 per year, and could lead full, productive lives ... Despite this evidence, there is a treatment gap for epilepsy which means that more than 50% of people with epilepsy in most LMIC (low- and middle-income countries) do not receive the treatment they need."

You can read the WHO report here.

Carbon dis-credit: How credible is the carbon market?

The U.K. Parliament's Briefing "Blue Carbon" tells us that the U.K. is "legally committed to reaching net zero emissions of greenhouse gasses (GHGs) by 2050" explaining: "Marine ecosystems around the U.K. can both increase and decrease atmospheric carbon dioxide levels. Carbon loss and gain globally by these ecosystems has the potential to influence climate change."

In their POSTnote, they cite 93 research papers in order to give an overview of the marine ecosystems in the U.K. One of these papers is the open access article "Caught in between: credibility and feasibility of the voluntary carbon market post-2020," from the journal Climate Policy.

While the U.K. Parliament Brief gives a thorough overview, it also explains that many questions remain unanswered, pointing out that "marine ecosystems in the U.K. have an estimated total carbon sequestration rate of 11 million tCO₂e/year, although this value is very uncertain, and higher estimates exist."

Alongside this scientific uncertainty is also what they describe as "a weakly regulated" voluntary carbon market. The U.K. Parliament POSTnote asserts: "Carbon sequestration projects often employ blended finance, where projects are funded by a combination of public and private finance. In general, voluntary carbon markets are weakly regulated. This can cause problems for investors because they cannot trust the quality of carbon credits that they purchase."

In their open access paper, cited in the POSTNote, Nicholas Kreibich and Lukas Hermwille focus on that weak regulation, analyzing "the plans of 482 major companies with some form of neutrality/net zero pledge."

The researchers find a veritable can of worms: "All companies we analysed have announced some form of neutrality target, but many of the targets lack clarity in key aspects. Moreover, they differ in several ways: Some companies explicitly include all GHG emissions (climate or GHG neutrality), whereas others focus on CO2 emissions only (carbon neutrality). For 97 companies, it remained unclear which GHGs are covered in the commitment."

"Moreover, while most companies consider all direct and indirect emissions of their own operations, some companies seek to work with their business partners and even include emissions that occur further up or down the supply chain and are beyond their direct control ... Also, the pledges differ in their timing. While the vast majority of the companies included in our dataset have a 2050 horizon, some companies, including two of the largest companies in the list, Google and Microsoft, claim that they have already achieved carbon neutrality."

Read more in "Caught in between: credibility and feasibility of the voluntary carbon market post-2020."

Being smart about intelligent agriculture

The topic of artificial intelligence (AI) is so ubiquitous right now that a Google search brings up over a billion results. McKinsey analysts Michael Chui and Martin Harrysson sum up AI's importance: "AI is fast becoming an invaluable part of the human-development toolkit."

The European Parliament Panel for the Future of Science and Technology (STOA) has investigated AI's relevance to human-development, particularly as it relates to food production, with their 2023 study "Artificial intelligence in the agri-food sector." The report affirms that: “Artificial intelligence (AI) could be a powerful tool in helping organisations cope with … increasing complexity in modern agriculture. Intensive data collection paves the way for growers, and all other actors in the value chain, to adopt artificial intelligence as a data-driven practice to gain more insights and, ultimately, better control the processes that affect producer income.”

The study continues: “(AI may) lead to more efficient production and improve workers' wellbeing and animal welfare … AI is also an important tool for the automation and robotics that may relieve workers of drudgery.”

In the Executive Summary of the report, the authors acknowledge that there are ethical and policy issues that need to be addressed: "This study defines several issues that may require special measures or policy action to ensure all stakeholders have access to a fair and equitable participation in the benefits that AI may bring to agriculture."

"Artificial intelligence in the agri-food sector" cites 91 research sources, including the Taylor & Francis open access paper "Managing the risks of artificial intelligence in agriculture" from the journal NJAS: Impact in Agricultural and Life Sciences.

In their paper, authors Robert Sparrow, Mark Howard, and Chris Degeling "offer an initial survey, and evaluation, of the ethical, social, and policy issues that are likely to arise as AI begins to impact on agriculture."

The authors analyze current uses of AI in agriculture, as well as some of the proposed uses, along with highlighting "applications of AI in the broader society and economy that are likely to impact on agriculture." They also look at benefits, risks, and ethics.

The team of researchers concludes: "Key questions that we believe should be considered in such deliberations (of whether to implement AI or not) include: how to ensure AI is used to expand sustainable agriculture rather than simply to intensify existing, unsustainable, agricultural practices; how to respond to the prospect of widespread job losses in the agricultural sector in the longer term; the risk that AI will exacerbate rather than reduce inequality; who should own data generated by AI and what they should be allowed to do with it; how to ensure that relations between farmers, seed and chemical companies, and suppliers of AI systems are productive and not exploitative; and, the philosophical and cultural implications of coming to see the world solely through the lens of 'data.'"

You can read the European Parliament report here, and the Taylor & Francis study here.

Global collaboration is key to disaster response and reduction

According to the Emergency Events Database, in 2021, droughts, floods, and storms created global losses of more than $224 billion, impacting the lives and livelihoods of millions.

In its report "Charting a Course for Sustainable Hydrological and Meteorological Observation Networks in Developing Countries" the World Bank addresses the importance of having systems in place to protect people from these natural disasters: "The World Bank’s development agenda is intimately linked ... to hydromet (hydrological and meteorological) monitoring and forecasting to anticipate threats and opportunities posed by the environment. Application of this knowledge can ameliorate risks by protecting the vulnerable and reducing exposure."

The World Bank explains that it aims "to help nations and development partners design fit-for-purpose and fit-for-budget sustainable hydrological and meteorological networks, (with) recommendations (that) are based on successful outcomes in higher income nations."

One of the papers they cite is the open access article "Intergovernmental cooperation for hydrometry – what, why and how?" from the journal Hydrological Sciences Journal.

The researchers open their piece with the daunting statistic that "two-thirds of hydrological observation networks in developing countries are reported to be in poor or declining condition." However, they offer hope in the form of an innovative initiative, which their paper explores, called the World Meteorological Organization’s Global Hydrometry Support Facility, or WMO HydroHub. Educating policymakers, researchers, and others about this initiative is essential, because the authors contend: "For those outside the immediate ‘WMO Community’ ... awareness of how such an intergovernmental organization supports its Members and the tools it provides to society at large is sometimes less widespread. The mass of technical literature and network of interconnected initiatives can at first sight appear indecipherable."

The study concludes: "The expansion of partnership is a key step in realizing the ... achievements. This includes partnerships within the operational hydrometry community, with greater peer-to-peer support across National Meteorological and Hydrological Services (NMHSs) to address needs associated with water monitoring technologies, data management systems, and education and training. But, critically, it must also include much more collaboration between NMHSs and: (a) the communities developing innovative technologies; (b) regional water and disaster management organizations to facilitate data sharing and problem solving; (c) local water users to increase community engagement in water issues; and (d) national and transboundary entities tackling shared problems at large scales."

Read the World Bank paper here, and the open access Taylor & Francis research here.

Fixing the bugs when it comes to gene editing insects

Gene editing that inadvertently creates monsters has become a plot staple for many science fiction and horror movies and TV shows. This is no surprise, because it is still a relatively new technology that inspires a combination of fear and wonder, and mistakes – which tend to make sensationalist news headlines – do happen.

The importance of research when it comes to this awesome power of being able to change the very DNA of an organism cannot be overstressed. So science and evidence-based studies, such as "Gene editing and agrifood systems" from the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO), are crucial to providing insights on "the consequences for human hunger, human health, food safety, effects on the environment, animal welfare, socioeconomic impact and distribution of benefits."

Utilizing over 296 research outputs, including an open access article from the journal Critical Reviews in Biotechnology, the FAO paper gives this summary: "Gene-editing technologies represent a promising new tool for plant and animal breeding in low- and middle-income countries. However, as for any new technology, they have their merits and demerits. There is, as yet, no international consensus regarding if and how gene-edited organisms should be regulated."

The Taylor & Francis paper cited in "Potential use of gene drive modified insects against disease vectors, agricultural pests and invasive species poses new challenges for risk assessment" addresses that regulation when it comes to the modification of insect genes, and offers recommendations.

72% of the world's crops require insects for pollination, and up to 40% of global crop production is lost to pests annually, so having the ability to control insects has been on farmers' to-do lists for centuries.

Setting the scene, the researchers let us know that we are still in the very early stages of GDs (engineered gene drives): "While current research is investigating the development of engineered GDs in insect populations and deploying them, it will take many years before they can be applied to practical disease vector/pest management. At present, some GDMIs are either in development or have been tested experimentally in the laboratory, often with multigenerational data and model simulations. However, no “contemporary” GDMIs have been assessed in small-scale physically and/or ecologically confined field trials, or open release trials."

The risks they put forth for gene-modified insects include a shopping list of ecological disasters: unintended spread beyond the target population; human exposure to toxic substances through consumption of GD-modified individuals; reduced quality or eradication of the GD-modified individuals where they are a food source; altered water quality due to the suppression of the target organism from algal bloom; and resurgence of “an intrinsically harmful target organism due to future failure of an engineered GD (e.g. genetic and phenotypic instability) or resistance to either the GD or its cargo/payload genes, possibly coupled with reduced immunity in human populations that have had a reduced disease challenge while the control was effective."

They close their paper with practical recommendations for risk assessment: "To ensure that the risk assessment guidance for GDMOs is proportionate, practical and current, it may need to be tailored to the most likely cases moving to practical applications for release. It should also offer an overarching framework that is flexible and outlines general principles and methodology for risk assessment instead of being overly prescriptive. The process of guidance development must ensure an iterative process of design, revision, and refinement, including the review of actual case studies by risk assessment experts and consultation with relevant stakeholders."

Read the FAO study here, and the Taylor & Francis paper here.

Evidence-based research impacting policy

It is clear from these five examples that research, in particular open access STEM research, is indeed impacting policy.

It is wonderful that so much research is making it into the right hands, but much more needs to be done for those research papers published globally every year that do not have as much impact. D. Max Crowley and J. Taylor Scott, authors of The Social Side of Evidence-Based Policy advise that a new infrastructure needs to be built.

They explain: "Such an infrastructure may involve new roles for staff within policy organizations to engage with research and researchers, as well as provision of resources that build their capacity to do so. For researchers, this infrastructure may involve committing to ongoing, mutual engagement with policymakers, in contrast with the traditional role of conveying written results or presenting findings without necessarily prioritizing policymakers’ concerns. Intermediary organizations such as funders and advocacy groups can play a key role in advancing the two-way streets through which researchers and policymakers can forge closer, more productive relationships."

Utilizing a theoretical framework proposed by Sarah Chaytor at University College London (UCL), the Higher Education Policy Institute (HEPI) and Taylor & Francis have published a policy note that provides five functional elements for action for academia, decision makers, industry, publishers, and the wider public to support research impact.

Highlights of the policy note include:

- Moving "away from rewarding competition to encouraging and crediting collaboration, openness, and transparency in the research and publication process"

- "Giving credit for a wide range of contributions and contributors to research that have been historically 'hidden' from more traditional research assessment exercises"

- "Recognizing the diversity of research outputs and contributions, valuing engagement with a diversity of audiences, and crediting researchers who openly and transparently share the outcomes of their research process."

You can find the policy note "Why Open Access is not enough – how research assessment reform can support research impact" on our Research Impact Hub.

It's also important to note that what we consider to be "research impact" is evolving, and will continue to do so.

Times Higher Education, for example, has challenged the traditional interpretation of impact, assessing universities on a combination of research, stewardship, outreach, and teaching, with their Impact Rankings. They are "the only global performance tables that assess universities against the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs)," taking into account "differing national, regional and local contexts. This critical examination of how we look at research impact is a step in the right direction, to ensure that researchers will get credit for the important work they do, regardless of the prestige of their institution, or where they are in the world.

You might also like:

Social justice and sustainability

Find out about the content we publish, commitments we've made, and initiatives we support related to social justice and sustainability:

China

China Africa

Africa