Racism and healthcare: an urgent call to care, confront, and correct

By Leah Kinthaert

The theme for this year’s Black History Month (US) is Black health and wellness.

The Association for the Study of African American Life and History (ASALH®) tells us: “In the still overhanging shadow of the COVID-19 pandemic, Black people should and do use data and other information-sharing modalities to document, decry, and agitate against the interconnected, intersecting inequalities intentionally baked into systems and structures in the U.S. for no other reason than to curtail, circumscribe, and destroy Black well-being in all forms and Black lives.”

"What is apparent from every single one of these studies is that institutionalized racism in healthcare is by no means a thing of the past, but unfortunately is alive and well."

Utilizing the latest research published by Taylor & Francis, I did a survey of articles on the topic of racism and healthcare, utilizing sources from journals related to sociology and social work, to medical education and policy. What is apparent from every single one of these studies is that institutionalized racism in healthcare is by no means a thing of the past, but unfortunately is alive and well. Healthcare professionals and policy makers need to learn from the stories of Black men and women on both the giving and receiving end of healthcare.

Attention also must be paid to the fact that the concept of “healthcare” should not be a narrow focus that begins and ends on the clinic visit, but should incorporate a wholistic approach – from ensuring healthy living conditions for all – to raising the awareness of the existence of inequities - so racism can be addressed and brought to an end.

Photo of Philadelphia street by Kelly L via Pexels.com

Photo of Philadelphia street by Kelly L via Pexels.com

Medicine’s social contract: only for white people?

As Nicole Rockich-Winston et al. point out in "All Patients Are Not Treated as Equal”: Extending Medicine’s Social Contract to Black/African American Communities (Teaching and Learning in Medicine): “historical examples of medical experimentation and mistreatment suggest that medicine’s social contract has not been extended to Black patients”, explaining “because underlying medicine’s contract with society is another contract; the racial contract, which favors white individuals and legitimizes the mistreatment of those who are nonwhite.”

The iconic (and stereotypical) image of a white man in a white coat wearing a stethoscope instills more fear than trust for many, depending on your race and socio-economic status. This wariness and suspicion has been front and center during the COVID-19 crisis, when Black and Latin communities in the United States were widely reported to have lower vaccination rates. In 'It’s not the science we distrust; it’s the scientists’: Reframing the anti-vaccination movement within Black communities (Global Public Health) Krystal Baatelan explains: “The anti-vaxx movement is often associated with conspiracy theories and dismissed as being ‘anti-science’. However, scepticism from Black communities must not be read as being ‘anti-science’, but rather ‘anti-scientist’ due to endemic racism in medical communities and structural inequalities in healthcare.”

Photo Suzy Hazelwood via Pexels.com.

Photo Suzy Hazelwood via Pexels.com.

Photo by Markus Winkler via Pexels.com.

Photo by Markus Winkler via Pexels.com.

Bad medicine: A sordid history of sterilization, experimentation, and supression

Baatelan provides a gripping and succinct history lesson for those who might not immediately understand this ‘anti-scientist’ sentiment: “Some of the scepticism toward the development of a COVID-19 vaccine is rooted in the anti-Black violence and exploitation that occurred in western biomedicine historically. Enslaved Africans were frequently used for medical experimentation due to their ‘availability’ and lack of rights, a practice that continued long after slavery legally ended.” Baatelan continues: “Black people were experimented on, forcibly sterilized, denied health insurance” and, due to often living in poor communities where they were victimized by a healthcare system, they “were unable to question white doctors because they could be turned away from hospitals due to the nature of the Jim Crow era." It is in this setting, for example, that the HeLa cells of Henrietta Lacks could be taken without informed consent; Black men could be callously observed, go untreated, and left to die of syphilis, in the Tuskegee Study; and 60,000 people could be sterilized based on ‘eugenics’ theories. Additionally, there is disturbing data showing that inequities in sterilization are not a thing of the past, as documented in Loretta Bass’ Living in the American South and the Likelihood of Having a Tubal Sterilization (Sociological Focus).

A tale of two celebrities: Eazy E and Magic Johnson

“The production of social space” and “racialized poverty” are factors which Krystal Baatelan says create a fertile environment for the spread of infectious disease, whether that be the flu, COVID-19 or HIV. Baatelan argues in her 2020 paper for Social Identities: Journal for the Study of Race, Nation and Culture, 'When whites catch a cold, black folks get pneumonia': a look at racialized poverty, space and HIV/AIDS: “Black people have been disproportionately confined (in dense urban areas); approximately 23% of African Americans in the US live in poverty, compared to 13% of all Americans. Additionally, 33% of Black children live in poverty compared to 18% of all Americans. Although African Americans represent 13% of the US population, they account for 43% of HIV diagnoses. Therefore, rates of infection for African Americans are disproportionately high because they are more likely to live in poverty.” Baatelan’s paper analyzes the lives of two wealthy and famous Black men, Magic Johnson and Eazy E; Baatelan gives details as to why Magic Johnson, who grew up in a safe, stable home with access to necessary resources, was able to live a healthy life after contracting HIV thirty years ago, while Eazy E who “grew up in a violent, racist neighbourhood, where access to resources such as healthcare and an adequate education were difficult to obtain”, succumbed to the disease in 1995 at the age of 31.

Baatelan cites a dire shopping list of hazards that she contends contributed to Eazy E’s death, from lack of healthcare for his asthma, to beatings from police in several encounters, to substandard housing in an area where he was potentially exposed to high levels of toxins, high stress, and poor nutrition. A 2019 Economic Policy Institute study provides a similar analysis, explaining that “beginning in infancy, lower social class children are more likely to have strong, frequent, or prolonged exposure to major traumatic events, the frightening or threatening conditions that induce a stress response” and “independent of other characteristics, children exposed to more frightening and threatening events are more likely to suffer from academic problems, behavioral problems, and health problems.”

Substandard housing conditions can expose children to high levels of stress and toxins; additionally poor neighborhoods are typically "food deserts". Photo courtesy Tim Huffner via Unsplash.com.

Substandard housing conditions can expose children to high levels of stress and toxins; additionally poor neighborhoods are typically "food deserts". Photo courtesy Tim Huffner via Unsplash.com.

Why ER (everyday racism) leads to the ER: crucial preventive health screenings delayed

Lastly, Baatelan maintains that Eazy E’s delay in seeking treatment factored into his death from HIV and was “reflective of his lack of trust in institutions, and unfair treatment of Black people in healthcare due to the highly racialized nature of Compton where he grew up”. This tendency to delay seeking care is also documented in the Wizdom, Powell et al. Medical Mistrust, Racism, and Delays in Preventive Health Screening Among African-American Men article from the journal Behavioral Medicine.

In this study, “analyses were conducted using cross-sectional data from 610 African-American men aged 20 years and older recruited primarily from barbershops in four US regions”; the authors explain that there is a great deal of speculation about medical mistrust, and explain why there is medical mistrust (it’s often attributed to the Tuskegee Study and the deep legacies of racism), but stress that a study of this kind has never been done to their knowledge. Also scarce are “quantitative studies of preventive health screening use in nonclinical populations of African-American men”.

Their study discovered that: “African-American men with more frequent 'everyday racism' (ER) exposure had higher odds of delaying blood pressure screening and routine healthcare visits. This finding… suggests frequent ER experiences may lead African-American men to avoid healthcare institutions partly because of stigma-induced identity threat… our findings further infer that accumulated negative lived experiences also become prisms for viewing and making preventive health choices. In other words, it is probable that frequent 'everyday racism' (ER) experiences accumulate, induce expectations of unfair treatment, and exact ‘wear-and tear’ on African-American men’s trust in medical organizations.”

“A little patient-centeredness could go a long way”

They see a light at the end of the tunnel: “Even in the face of a ‘wicked problem’ like ER, medical mistrust may be modifiable. In fact, research affirms that African-American men report lower medical mistrust when they also report having a more recent, patient-centered physician interaction. Patient-centered interactions are characterized by mutuality as well as supportive and responsive communication and are associated with higher patient trust in other populations. Yet, fewer African-American patients report having these kinds of physician interactions compared to White patients.

Wisdom, Powell et al. advise: “For African-American men, who are disproportionately exposed to daily, racialized slights against their humanity, a little patient-centeredness could go a long way in restoring their medical organization trust, as well as improving timely detection and screening.” They wrap up their article with this lesson for caregivers: “Dismantling racism inside and outside of the healthcare system is a vital part of reducing preventive health screening delays and ultimately eliminating health disparities in African-American men.”

Marchers with signs at the March on Washington, 1963. Negative by Marion S. Trikosko, 1963. Photo from Library of Congress via Unsplash.com.

Marchers with signs at the March on Washington, 1963. Negative by Marion S. Trikosko, 1963. Photo from Library of Congress via Unsplash.com.

Photo by Markus Spiske at Unsplash.com.

Photo by Markus Spiske at Unsplash.com.

Mural of musicians Eazy E and Dr. Dre in Compton, California. Photo by Jonathan Kaufman via Unsplash.com.

Mural of musicians Eazy E and Dr. Dre in Compton, California. Photo by Jonathan Kaufman via Unsplash.com.

Studies of preventative health screening in nonclinical populations of African-American men are scarce. Photo whoislimos via Unsplash.com.

Studies of preventative health screening in nonclinical populations of African-American men are scarce. Photo whoislimos via Unsplash.com.

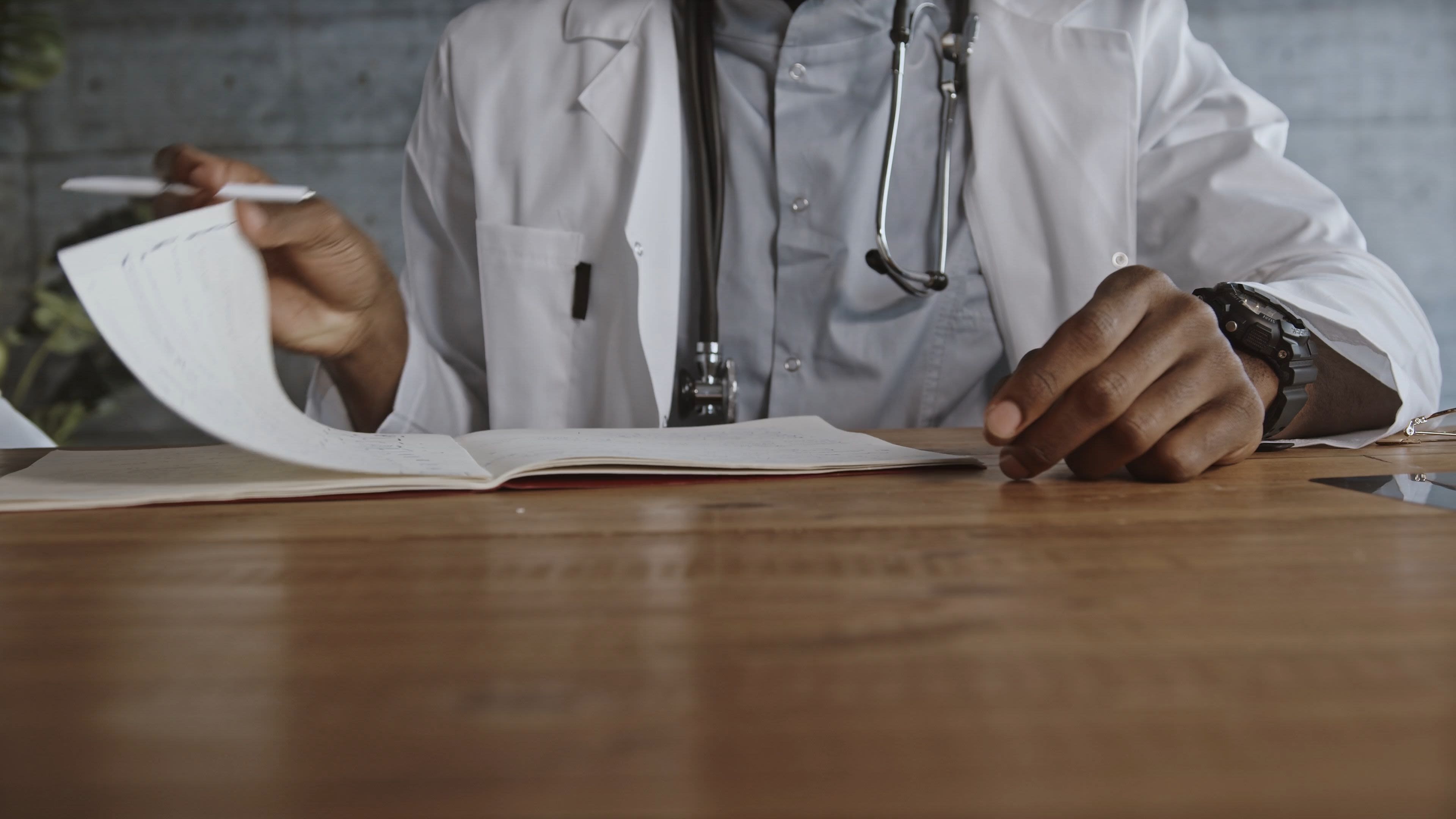

Study: "African-American men report lower medical mistrust when they also report having a more recent, patient-centered physician interaction." Photo NCI via Unsplash.com.

Study: "African-American men report lower medical mistrust when they also report having a more recent, patient-centered physician interaction." Photo NCI via Unsplash.com.

COVID-19 disproportionately affecting black communities

According to the latest data from the CDC and the Kaiser Family Foundation, the vaccination gap this article mentioned earlier between White and Black communities has narrowed. Nambi Ndugga et al. write: “Over the course of the vaccination rollout, Black and Hispanic people were less likely than their White counterparts to have received a vaccine, but these disparities have narrowed over time, particularly for Hispanic people.” They continue: “The increasing equity in vaccination rates likely reflects a combination of efforts focused on increasing vaccination rates among people of color through outreach and education and reducing access and logistical barriers to vaccination, increased interest in getting the vaccine due to spread of the Delta variant, and increases in vaccinations among younger adults and adolescents who include higher shares of people of color compared to other adults.”

While this is promising news, there is still the appalling reality that COVID-19 has been particularly lethal in Black communities. Baatelan cites data from Toronto and Chicago to prove her point: “According to the latest data from the city of Toronto, racialized people make up 83% of reported Covid-19 cases while only making up half of Toronto’s population. Black people make up 21% of reported cases in the city while making up only 9% of the population” and “in Chicago, African Americans make up around 30% of the population, but have made up approximately 72% of Covid-19 related deaths.”

Race trumps class when it comes to death from COVID-19

Darius Reed’s study on COVID-19 in the Maryland community of Prince George’s County differs from these other studies a bit in his analysis, as race trumps class in his Social Work in Public Health article: Racial Disparities in Healthcare: How COVID-19 Ravaged One of the Wealthiest African American Counties in the United States. Reed follows the money, and finds disparities where “public funding is not equally distributed regardless of wealth and status for minoritized communities”. Reed describes Prince George’s County: “Long regarded as a symbol of Black wealth and excellence with a high population of highly educated Black professionals, entrepreneurs and government officials, where African Americans make up 65% of households and the median household income is 81,969 USD.” In this wealthy county however, COVID-19 and death from COVID-19 was disproportionately high in 2020, because “many residents are front-line workers exposed daily to the virus, and Prince Georgians disproportionately suffer from underlying health conditions that make the virus deadlier.” This is significant, because while 40% of U.S. healthcare workers are people of color, in July 2020 they made up more than half of confirmed COVID-19 cases. The Kaiser Family Foundation writes:"people of color accounted for a majority of COVID-19 infections, hospitalizations, and deaths known among health care workers for which race/ethnicity data is available."

Digging a bit deeper, Reed finds that “despite high per capita incomes, Prince George’s County spends less on health and human services than its neighbors. With 38.94 USD per capita in general fund investment, it falls behind others like Baltimore County, which spends 45.13 USD; Anne Arundel, at 90.54 USD; Howard County with 109.37 USD; and Montgomery County with 224.25 USD.” Additionally, African American communities lack supermarkets that sell fresh healthy food: “Black neighborhoods have significantly fewer supermarkets than white ones and Prince Georges County is no different despite its wealth status.”

Reed’s plea is for policy makers to “understand the depth of healthcare disparities for people of color”. He concludes: “The lack of PPE, inconsistent access to healthcare due to lack of insurance or underinsurance, chronic health conditions in communities of color, and crowded living conditions is not only troubling, but indictive of the lack of governmental investment and oversight for communities of color.”

Photo by RODNAE Productions at Pexels.com.

Photo by RODNAE Productions at Pexels.com.

Photo from CDC via Unsplash.com.

Photo from CDC via Unsplash.com.

A pathway to the future

In their article, Structural Racism in the COVID-19 Pandemic: Moving Forward in The American Journal of Bioethics, Maya Sabatello et al. offer what they call a “pathway to the future” with “community engagement to develop culturally-sensitive responses to the myriad genomic/bioethical dilemmas that arise, and the establishment of a Truth and Reconciliation Commission to transition the country from its contemporary state of segregation in healthcare and health outcomes into an equitable and prosperous society for all.” They also offer more data on racial disparities: “Although the infection rate in the nation’s poorest neighborhoods is twice as it is in the wealthiest neighborhoods, it is the racial and ethnic disparities that are paramount. Emerging data show that Blacks/African Americans (AAs), Latinxs and American Indians/Alaska Natives (AI/ANs) are far more likely than non-Latinx Whites to be sickened and to die from COVID-19, and the rates are staggering.”

The anti-science skepticism Baatelan discussed comes to the forefront again here, as a vulnerable communities, already understandably mistrusting the powers that be, get their fill of more mistreatment and neglect. Sabatello writes: “With the disproportionate effects of the pandemic on racial and ethnic minorities, it is conceivable that members of such communities will choose to further disengage from biomedical research and the healthcare system that has failed them.” Sabatello et al. advise the healthcare researchers use utmost ”caution in enrollment of racial and ethnic minorities” and to use COVID-19 as a way to challenge long established, but unethical, research practices. On a positive note, Sabatello et al. do see COVID-19 as giving a “face to decades of segregation, racism and structural discrimination. It forces us to look to the generations of especially Blacks/AAs, Latinxs and AI/ANs that have often endured mistreatment in all aspects of life—from limited educational and employment opportunities to high levels of poverty and environmental neglect, insufficient, often absent, access to basic healthcare services, police brutality, and overrepresentation in the criminal justice system.”

Paying the “minority tax”

In their paper "All Patients Are Not Treated as Equal”: Extending Medicine’s Social Contract to Black/African American Communities Nicole Rockich-Winston et al. touch upon the double burden that clinicians of color have: “much of the work around diversity currently falls on the shoulders of minoritized faculty who are often unacknowledged for their extra efforts to address the country’s racial contract. Their sense of responsibility in addressing the racial contract is one of the many ways Black/African American physicians are unfairly burdened with a minority tax.” The researchers advise: “Leaders must understand that the burden of extending the social contract to all patients is not solely the work of Black physicians; it is the responsibility of the profession itself, as it is medicine and its practices have supported the racial contract within the profession. Presently, this work is challenging because so many white physicians are unaware of the medical experimentation and mistreatment of Blacks/African Americans, and the need to incorporate these perspectives in the training of physicians.”

In their article "What Does it Cost to be a Black Bioethicist?" for The American Journal of Bioethics blog, Keisha Ray PhD and Faith E. Fletcher PhD explain how the “minority tax” has implications for specifically Black bioethicists: “Because diverse voices and perspectives are critical to advancing institutional agendas, Black bioethicists are frequently asked and often expected to engage in DEI work—labor that is generally not compensated or credited in tenure and promotion decisions. Disproportionately heavy workloads germane to Black faculty can lead to unfair perceptions, biases, stereotyping and ultimately labeling Black scholars as overextended, overwhelmed, not focused, spread too thin, unreliable with deadlines and incompetent. Without adequate institutional support structures, DEI work can cause mental and emotional trauma, fatigue and burn-out.”

They offer advice to institutions and organizations: ”To mitigate these costs, institutions and organizations should compensate Black bioethicists for DEI-related work and strategically work to change institutional policies and practices by prioritizing DEI work in promotion and tenure decisions.”

Photo by CDC via Unsplash.com.

Photo by CDC via Unsplash.com.

Another viewpoint on race

While so many studies I have cited assume that looking at Black vs. White vs. other groups is an important factor in making change, Ruqaiijah Yearby offers another view, and wants us to challenge our very idea of “race”. In her paper Race Based Medicine, Colorblind Disease: How Racism in Medicine Harms Us All published in The American Journal of Bioethics, Yearby challenges the status quo: “The genome between socially constructed racial groups is 99.5%–99.9% identical; the 0.1%–0.5% variation between any two unrelated individuals is greatest between individuals in the same racial group; and there are no identifiable racial genomic clusters. Nevertheless, race continues to be used as a biological reality in health disparities research, medical guidelines, and standards of care reinforcing the notion that racial and ethnic minorities are inferior, while ignoring the health problems of Whites," adding that "race should only be used as a factor in medicine when explicitly connected to racism or to fulfill diversity and inclusion efforts.”

Yearby by no means suggests “the adoption of a colorblind approach in medicine” but asserts that data collections must be far more rigorous, in order to discontinue a classification system she considers inherently racist. She recommends: “Instead of using race (biological and social) as a measure for health disparities research, medical guidelines, and standards of care, I suggest using the social determinants of health and other factors, including but not limited to: neighborhood (based on zip code); education; occupation; job; health insurance coverage; income; wealth; health behaviors; experiencing racism; gender identification; disability status; and age.”

Photo by Ehimetalor Akhere Unuabona via Unsplash.com.

Photo by Ehimetalor Akhere Unuabona via Unsplash.com.

Photo Tima Miroshnichenko via Pexels.com.

Photo Tima Miroshnichenko via Pexels.com.

"you have within you the strength, the patience, and the passion to reach for the stars to change the world."

I titled this piece "Racism and healthcare: an urgent call to care, confront, and correct” after I did the research, and I hope within these paragraphs I have shown care, and confronted the issues by providing several important studies. Next steps are that I hope people reading this with the power and influence to “correct” take heed of the advice given by these researchers. Firstly, patient centricity is key as a way of ensuring all individuals get necessary preventative care. Secondly, disparities in per capita investment in healthcare need to be addressed and ceased. Thirdly, the burden of dealing with racism needs to be shouldered by a broader community than just people of color. We invite you to learn more with these resources on racism and its intersections with healthcare at the link below.

China

China Africa

Africa