Women healers: from ancient female shamans to 21st-century doulas

By Leah Kinthaert

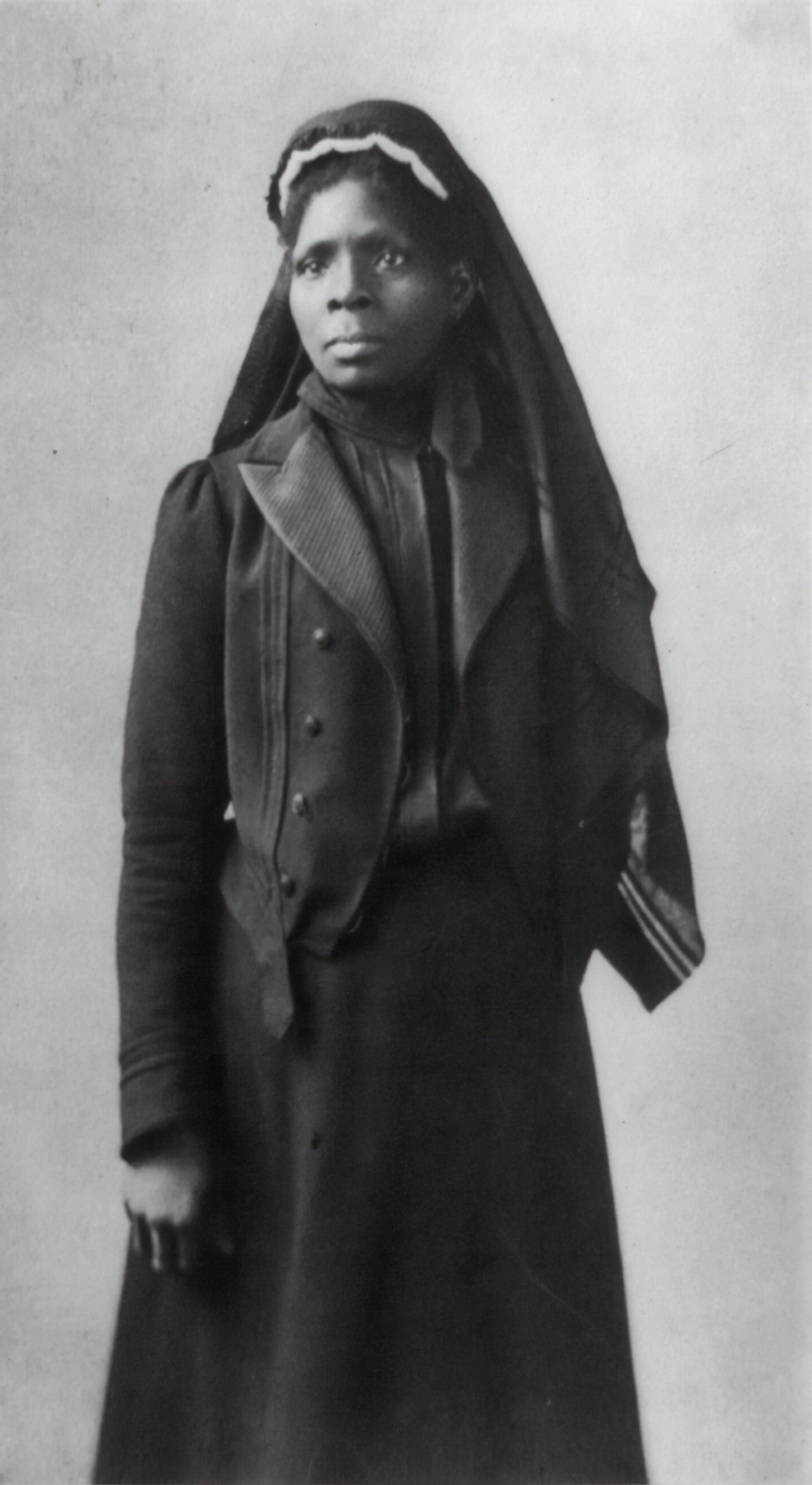

Susie King Taylor was the first African American Army nurse. Library of Congress via Unsplash.com.

Susie King Taylor was the first African American Army nurse. Library of Congress via Unsplash.com.

Mother and child in Sierra Leone. Photo by Annie Spratt via Unsplash.com.

Mother and child in Sierra Leone. Photo by Annie Spratt via Unsplash.com.

Photo Kampus Production via Pexels.com.

Photo Kampus Production via Pexels.com.

Photo from NCI via Unsplash.com.

Photo from NCI via Unsplash.com.

The theme for Women’s history month this March from the National Women’s History Alliance (US) is: “Providing Healing, Promoting Hope”.

They explain on their site that: “Women as healers harken back to ancient times…women… have historically brought these priceless gifts (of healing and hope) to their families, workplaces, and neighborhoods, sometimes at great sacrifice. These are the women who, as counselors and clerics, artists and teachers, doctors, nurses, mothers, and grandmothers listen, ease suffering, restore dignity, and make decisions for our general as well as our personal welfare.”

To honor women in their many functions as alleviators of pain, curers of the sick, menders of minds, and rejuvenators of souls, this month, we dove into this fascinating topic, “Women Healers”, with a survey of the latest research published by Taylor & Francis.

All the work, little of the credit

Ofonmbuk Esther Ekong tells us that “three-quarters of the world’s population depends upon traditional remedies for their health (according to the World Health Organization (WHO).”

I will add to the findings from the United Nations report “The World’s Women 2020: Trends and Statistics”: “On an average day, women globally spend about three times as many hours on unpaid domestic and care work as men (4.2 hours compared to 1.7).

In Northern Africa and Western Asia that gender gap is even higher, with women spending more than seven times as much as men on these activities”.

This tells a story, that globally, it is women that are doing the healing, with, in most cases, traditional remedies. And when it comes to what we commonly refer to as “healthcare” - or non-traditional, non-indigenous, medicine - women make up over 70% of the workers, too. What is key here is that while women are doing most of the health-related work, they are not getting the status, although that is slowly changing.

This OECD report tells the story of women doctors: worldwide the share of female doctors was 29% in 1990, growing to 38% in 2000 and 46% by 2015. However, data suggests that "even when female workers pursue higher skilled professions in the medical profession, they tend to be underrepresented in the jobs with the highest earnings."

During the second wave of feminism in the 1970s, Women’s Studies was born, to study topics such as race, class, gender, and sexuality, in departments as varied as history, sociology, literature, politics, and psychology, with the goal of changing the position of women in the world. Taylor & Francis imprints Routledge and (prior to 2005) Carfax were some of the founding forces in gender studies and helped to bring together communities through their books and journals program.

It is in this multidisciplinary field that we find scholars surfacing the stories behind the numbers, the herstory of women as healers, as well as women’s role as healers today.

The Age of Reason wasn’t a very reasonable time for a woman healer

In Witches, Charlatans, and Old Wives: Critical Perspectives on History of Women’s Indigenous Knowledge from the journal Women & Therapy, Oksana Yakushko asserts: “over vast spans of Western history, women healers were branded as witches and punished for practicing witchcraft as well as denied influential healing roles because of the political and economic monopolization of knowledge in academic, religious, and cultural institutions and practices through enforcement of regulations and access to care. Moreover, centuries of European colonization of other cultures around the globe resulted in re-shaping these cultures away from traditions of women healers, women-shamans, and women-leaders toward male dominance of these fields.”

Yakushko provides a brief chronicle of events, citing several instances in her timeline where history has been erased, those in power have committed “intentional denial of women’s access to healing knowledge or positions”, or women were outright murdered for crossing the patriarchal lines. Some instances, in particular, stand out, such as “the earliest known evidence of shamanic practice found by archeologists, dating from more than 30,000 years ago, indicated that the shaman was a woman” and the dictum “who knows how to heal knows how to destroy”, from The Malleus Maleficarum, used as a macabre manual, during the infamous witch hunts.

The irony is palpable as Yakushko continues her history lesson: “The witch-hunts of Europe were so severe that historians estimate that hundreds of thousands of women were tortured, drowned, hung, or burned at the stake in a span of three centuries (XV to XVII centuries)… In contrast, history books written by males claimed this period to be the end of the Dark Ages, described as the Renaissance, and claimed to mark the rise of the Age of Reason.”

The demonization of women healers certainly didn’t stop when the witch trials did. In her look at 19th-century American popular fiction, in"Cutting Up Dead Babies”: The Literary Legacy of the Woman Physician as Abortionist from the journal Women’s Studies, Margaret Jay Jesse finds a great deal of it.

Jesse writes: “’Murderess,’ ‘hag,’ ‘she-devil,’ ‘the instrument of the very vilest crime known in the annals of hell’ – these are just a few descriptions of women abortionists in popular nineteenth-century American fiction… nineteenth-century sensational dime novels are flush with the character of the evil woman doctor: the greedy, swarthy, foreign-born doctress, performing abortions under the cover of night, harming and killing desperate Anglo-American women and their unborn babies all in the name of profit”.

Through a Western lens

Yakushko explains why there is so little historical information about women as healers outside of Europe: “Documented historical accounts of non-Western pre-colonization cultures show that women healers were present and honored, but that European invasions over the past seven centuries were especially marked by transmission of patriarchal religious and social norms. Moreover, available recorded precolonization history with regard to other cultures is presented through a Western lens, especially a Western male lens. However, contemporary critical historians have developed alternative accounts of this history and show that European colonizers not only shaped social gender relations in every culture they invaded, but distorted accounts of cultures prior to their arrival. Specifically, upon their arrival, European imperial explorers not only refused to speak to any women who held power in indigenous native communities, literally granting power exclusively to males, but they also interpreted cultural practices, symbols, and stories through their patriarchal Western perspectives. For example, religious importance of female deities, women-focused rituals, and women’s roles as healers were often interpreted as demonic... indigenous forms of healing, specifically by women, were perceived as a threat to new colonial powers and were especially targeted.”

“Despite the historical persecution and extermination of indigenous healers, indigenous healing practices have persisted around the globe and appear to have survived the onslaught of Western ‘scientific’ knowledge and practice”, writes Yakusho. Indeed, they are thriving.

“Women's physical, mental, and emotional natures made them unfit for work as doctors”

Laura Kelly recounts that the King and Queen's College of Physicians in Ireland “was the first institution in the United Kingdom to take advantage of the Enabling Act of 1876 and admit women to take its medical licences.”

Prior to that, Kelly tells us that “women had practiced informally as doctors in the early modern period”, but the powers that be had successfully used bureaucratic loopholes to make practicing medicine inaccessible for them.

Kelly writes in ‘The turning point in the whole struggle’: the admission of women to the King and Queen's College of Physicians in Ireland in the journal Women’s History Review: “the increasing formalization of medical education led to their increasing exclusion and the Medical Act of 1858 gave the force of statutory law to the increasing exclusion of those who had not undergone approved courses of training and obtained qualifications entitling them to practice. This act essentially resulted in the re-organization of the medical profession and enforced the exclusion of outsiders. The act did not specifically exclude women but with the emphasis now placed on standardization of medical qualifications from universities, to which women had no access, it effectively prevented women from making it onto the Medical Register.”

The medicalization of birth

While I have shown you instances where women have been denied their rights to be healers, in the 20th and 21st centuries women have also been legally hindered in their right to give birth on their own terms, and in their own homes, or receive the help of other women to do so.

Jessica C.A. Shaw writes, in her paper The Medicalization of Birth and Midwifery as Resistance in the journal Health Care for Women International: “The medicalization of birth in Canada is a process that took place over much of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, and it continues today.

"Characterized by a physician-lead, highly interventionist model of care, medicalization has taken the natural ability to labor and give birth away from women. This is problematic because unnecessary medical interventions during labor and birth can compromise the safety and emotional well-being of both the mother and baby. Furthermore, by normalizing technological births, the concept of childbirth has changed to reflect a paternalistic, physician-led event where women are expected to be submissive."

“Women of color… must be diligent so as not to become dehumanized”

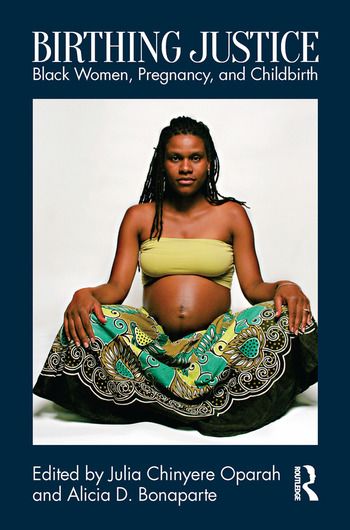

In “I Am My Hermana’s Keeper: Reclaiming Afro-Indigenous Ancestral Wisdom as a Doula” from Birthing Justice: Black Women, Pregnancy and Childbirth, Griselda Rodriguez explains why, as an Afro-Latina, being a doula is a political act:

“Doulas of color… help women navigate a health-care system that can disempower them if they are not prepared to stand up for their rights. It is a system that… was founded on patriarchal and racist doctrines that deemed non-European, nonmale, nonelite bodies impure and pathological. Women of color are therefore readily marginalized within this paradigm and must be diligent so as not to become dehumanized.”

Rodriguez continues: “As a doula of color, my role goes beyond serving as an emotional companion. I am often a cultural broker, a translator, and a buffer against the forms of neglect that often lead to unnecessary medical interventions and traumatic birth experiences for women. C-section rates skyrocketed from 4.5 percent of US births in 1965 to 32.8 percent in 2012. Between 1996 and 2009, the US C-section rate rose 60 percent from the most recent low of 20.7 percent, reaching a high of 32.9 percent of all births. As a result of a broken maternal-health-care system, the United States ranks fiftieth among fifty-nine developed countries for maternal mortality, and maternal mortality rates have actually increased since the mid-1980s. Sadly, but not surprisingly, things are worse for working-class women of color, (according to the study “Unequal Motherhood: Racial-Ethnic and Socioeconomic Disparities in Cesarean Sections in the United States” from Louise Marie Roth and Megan M. Henley): ‘African American women die from pregnancy-related causes more often than other racial-ethnic groups, and have a fourfold greater risk of maternal death than non-Hispanic white women. . . . Latinas and non-Hispanic white and Asian women all share similar rates of maternal mortality, although rates appear to be rising among U.S.- born Hispanics’.”

In 2020, Andrea Nove PhD et al. estimated that “even a modest increase in coverage of midwife-delivered interventions could avert 22% of maternal deaths, 23% of neonatal deaths, and 14% of stillbirths, equating to 1·3 million deaths averted per year by 2035.” The movement of Black women working to help their communities by being midwives and doulas has begun to make a marked difference, The Guardian reported on Roots Community birth center in Minneapolis, that “the birth center had no preterm births among its African American clients in 2017, and a primary caesarean rate of 3%”. Midwife Rebecca Polston explained to The Guardian: “Culturally, white providers are trained to pathologize people of color and to not believe them… So when people are able to be culturally intact – I don’t mean just a placeholder person of color, but someone who’s able to practice with cultural authority – they’re able to cut through that and actually care for the person.”

Redefining ‘invention’ for the community of women healers in Africa

A traditional healer is: “a person who is recognized by the community in which she lives as competent to provide health care by using vegetable, animal and mineral substances as well as spiritual therapies, manual techniques, and exercise; who relies exclusively on past experience and observation handed down from generation to generation, verbally or in writing.”

In the African Journal of Science, Technology, Innovation, and Development, Ofonmbuk Esther Ekong has conducted extensive research with women healers in Nigeria, and is concerned that although these women make a massive impact on innovation and healthcare in that country, they are being left behind when it comes to economic growth.

“Analysis from institutions like the World Bank and International Monetary Fund (IMF) demonstrate the economic growth potential that follows from increasing women’s labor force. This has led to the adoption of reforms by governments all over Africa to increase women’s ability to contribute to their economies. One type of business that women are actively engaged in is the art of traditional healing.”

She continues: “Women play key roles in the delivery of informal healthcare alternatives based on medicinal plants. The prevalence of women in this knowledge-based enterprise further underscores the role of women in sustainable development.”

Ekong advises that an international sui generis system should be created in order to protect these women’s livelihoods: “The patent law which has been crafted to fit this ‘scientific inventor’-newness, inventive and industrial application, sharply shuts out inventors like African traditional healers… There is therefore the need to redefine ‘invention’ for the purpose of patentability… It is important to include and carry out initiatives directed at women and girls in development if gender equality is to be achieved. One such initiative would be amending existing IP laws to include the unique innovations of women.” Ekong goes on to explain that there is a precedent in China of intellectual protection for traditional medicine, which Africa can adopt: “(Traditional Chinese Medicine)TCM has gained acceptance all over the world, including the United States where the National Institutes of Health recognizes it as an effective alternative medicine.

Part of the reason for such widespread success may be attributable to the intellectual protection strategy put in place by the Chinese government which may have incentivized traditional medicine practitioners to innovate more.”

Re-envisioning Western scientific paradigms

Professor Nuria Ciofalo practices her research with an acknowledgement and understanding that “psychology, as a legitimized discipline within Western scientific paradigms, has attempted to de-contextualize psychological phenomena and has produced universal theories based on White men’s regimes of truth”, instead she incorporates “indigenous psychologies (which) question the universality of existing Western scientific paradigms and incorporate context, meanings, values, beliefs, and vivencias (i.e., localized experiences in which knowledge is validated and legitimized by the same people who produce it) into research designs and knowledge generation.” Ciafalo’s advice to traditional psychology researchers is to question everything they know about their subject, and to elevate indigenous “ways of knowing and healing” to an equal footing with Western counterparts.

In Indigenous Women’s Ways of Knowing and Healing in Mexico from the journal Women and Therapy, Ciofalo explains: “Academia must not only integrate Indigenous women’s ways of knowing and healing as central part of its curricula, but also hire Indigenous women healers, respected as organic intellectuals and mentors for a new, emancipatory student generation. In this way, we may evidence the thriving of a promising generation that masters the application of inclusive approaches to improve and sustain individual, community, and cultural health and well-being. By invoking Ixchel and walking this road together as reciprocal mentors and apprentices, we will heal the wounds of our current system and replace it with buen vivir (well-being)."

Birthing Justice, Black Women, Pregnancy, and Childbirth. Edited By Julia Oparah, Alicia Bonaparte. Published by Routledge.

Birthing Justice, Black Women, Pregnancy, and Childbirth. Edited By Julia Oparah, Alicia Bonaparte. Published by Routledge.

Photo by Hussein Altameemi at Pexels.com.

Photo by Hussein Altameemi at Pexels.com.

The African Journal of Science, Technology, Innovation and Development, Volume 13, Issue 7 (2021)

The African Journal of Science, Technology, Innovation and Development, Volume 13, Issue 7 (2021)

Photo by Laura James at Pexels.com.

Photo by Laura James at Pexels.com.

You might also like:

Social justice and sustainability

Find out about the content we publish, commitments we've made, and initiatives we support related to social justice and sustainability: