What next in Ukraine?

Five experts outline possible military, political, environmental, and socioeconomic scenarios

10 June 2022

The rising tensions between Russia and Ukraine that followed the annexation of Crimea came to a head with Russia's invasion of Ukraine in February 2022.

Russia's decision to invade its neighbor was a dramatic – and surprising – watershed in the history between the two former republics of the Soviet Union.

We don't know how the conflict will end. But we do know it will have a significant and long-lasting impact on Ukraine and Russia.

So what's next in Russia's war and what could the future hold for Ukraine?

We asked five experts to outline possible scenarios:

- Dr. Nigel-Gould Davies and Dr. Frank G. Hoffman examine what could happen next in the conflict and its ramifications on Russia and Ukraine in the longer term

- Dr. Lowell Barrington tackles unity and democracy in a post-war Ukraine

- Dr. Kristina Hook explains the environmental impact of the war

- Dr. Hiroaki Matsuura highlights Ukraine's growing demographic crisis

"...when Ukraine and Russia believe the risks and costs of fighting exceed potential gains, there will be a genuine peace process"

Dr. Nigel Gould-Davies:

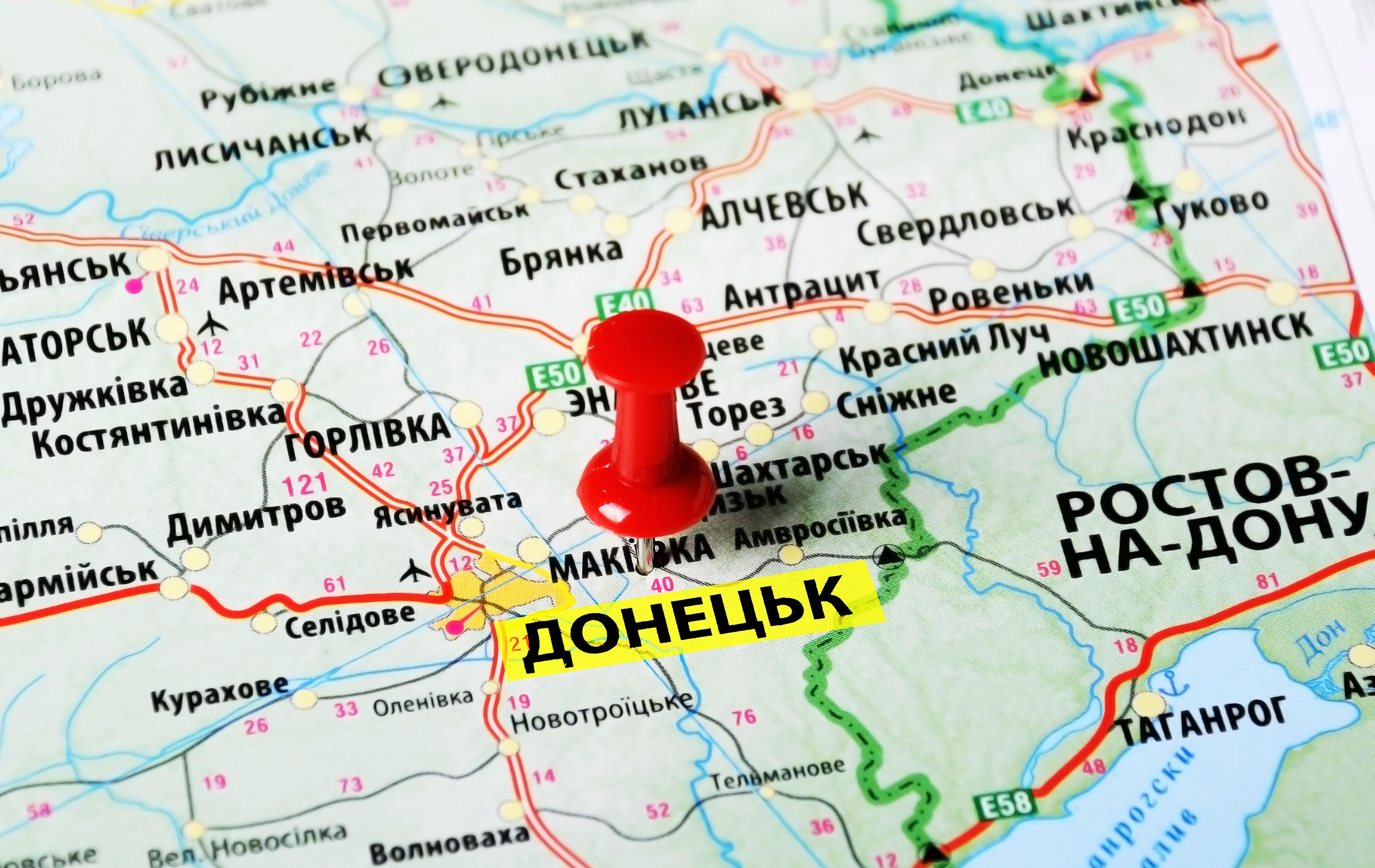

Ukraine and Russia are currently engaged in a fierce battle of attrition in the Donbas.

If Ukraine gains the upper hand and pushes Russian forces out of areas they have occupied since February, it will need to decide how much further it goes, and what the risks of doing so will be.

Will Ukraine seek to regain control over the so-called Donetsk and Luhansk People’s Republics? This is sovereign Ukrainian territory, but Russia may try to rush through a rigged referendum to annex it, and so claim that a Ukrainian advance constitutes an attack on Russia itself – even though such a claim will enjoy no international support.

Ukraine is also likely to seek to regain control of the areas of the south occupied by entrenched Russian forces and restore full access to its coastline. This will be a major challenge, but if Ukraine does not do so its economy will be permanently weakened. Russia will also use control of Ukrainian grain exports to bargain for the lifting of sanctions.

A peace process?

At some point, when Ukraine and Russia believe the risks and costs of fighting exceed potential gains, there will be a genuine peace process. The question of territorial control is only one of the issues in play. There are at least three others:

- The return of over one million Ukrainians forcibly taken into Russia

- Ukraine's right to join international organizations and the provision of security guarantees to it

- The financing of Ukraine's reconstruction – and Russia's responsibility for this, including the potential use of Russian financial assets seized by Western governments

War changes societies and politics. It shifts values and expectations, weakens old interests and institutions, and creates new ones. In ways no one can yet predict, Ukraine's post-war future will be shaped by the experience of national mobilization to defeat the invasion.

Like Putin, President Zelensky – whose standing has been transformed by the war – faces an election in March 2024. The election – assuming it can be held in safe, post-war conditions – will reveal much about these changes.

What about Russia?

The war has been a strategic disaster for Russia.

While the military outcome remains open, further Russian setbacks are more likely than recovery, let alone gains, at this point. Unless it makes a major gain, as Western military aid to Ukraine increases, Russia faces a steady adverse shift in the correlation of forces.

Russia must then choose whether and how to escalate. A national mobilization – which would require official acknowledgment that Russia is involved in a war and not a "special military operation" – would likely be unpopular and begin to erode the currently high level of support for Russia's aggression. Nonetheless, there are signs now that the authorities are preparing the ground for an unannounced, low-level form of mobilization. No version would provide significant new resources in the short term.

The war has been a strategic disaster for Russia.

Of the other escalation options potentially available to Russia, the least likely but most worrying is the use of nuclear or chemical weapons. Among other consequences, this would deepen Russia’s isolation and extend it indefinitely. Sanctions that the West and major Asian partners have imposed on Russia are already inflicting serious and cumulative costs. Russian use of weapons of mass destruction would lead to even more serious measures, as well as a range of other severe responses.

Even if Russia seeks to end the war to preserve any gains it has made – or curb further losses it faces – the fighting will only stop when Ukraine agrees to this. And there is no guarantee that a ceasefire, or even a peace agreement, will lead to the easing of sanctions on Russia. This is a decision for the West, which it will take in close consultation with Ukraine. Regardless of any peace settlement, war crimes investigations will continue.

The greatest uncertainty in an evolving situation full of uncertainties is the effect of the war on Putin's regime. When the scale of Russia's military losses becomes known, and sanctions cause widespread harm, popular support is likely to decline. The regime is now more authoritarian than at any time since the mid-1980s and is honing the instruments of repression to prevent mass opposition taking organized form.

The most interesting question is whether, against the background of failure and crisis, the regime itself will remain cohesive.

Dr. Nigel Gould-Davies is Senior Fellow for Russia and Eurasia at the International Institute for Strategic Studies (IISS). He conducts independent research and writes extensively on the politics, economics, and security of the former Soviet Union. He's the Editor of Strategic Survey: The Annual Assessment of Geopolitics and has published articles in the IISS's Survival journal.

"Another protracted, frozen conflict, bigger than Donbas of 2014, is the best result Putin can obtain"

Dr. Frank G. Hoffman:

Despite its lack of success in its planned blitzkrieg into Kyiv, Russian forces are now attempting to build on their more successful campaign along Ukraine's eastern frontier and its southern coastline. They may maintain a protracted offensive campaign. However, they will certainly demonstrate the same weaknesses and culminate well short of a strategic victory.

They may have improved some elements of their combat readiness, but it's very unlikely they learned enough from their pitiful performance so far, and many of their deficiencies (logistics and small-unit leadership) cannot be easily corrected in the near term.

More likely, another extended offensive will cost the Russian military dearly, and deplete their manpower and materiel resources. They are already facing significant losses in armored vehicles and manpower, attempting to pull in foreign fighters and mercenaries to augment the army. They also seem to be lacking a sufficient supply of precision munitions, thus the tendency to use massed artillery fire on fixed targets and civilian infrastructure.

Russia's sense of grievance against the West will grow larger...

If the Russians could mount assaults from their positions near Kharkiv and drive south to occupy the key city of Dnipro, they may isolate the best Ukrainian combat forces in a decisive battle. However, they will have to demonstrate better skills at combined arms maneuver than has been seen to date. Their units will have to employ initiative and manifest a will to fight that has been utterly absent so far.

The rolling and open terrain in the eastern portions of the country do create options for Russian mechanized operations. But there are a number of towns and cities in the Donbas that afford the Ukrainians good defensive redoubts and strong points needed to withstand Russian attacks.

Reinforcements

The Ukrainians, now reinforced with heavier weaponry from NATO countries, could replicate their defensive success from the early phase of the war and punish Putin's troops again.

Another protracted, frozen conflict, bigger than Donbas of 2014, is the best result that Putin can obtain. Even that will be a Pyrrhic victory that sets his country's economy and military back for a decade.

Putin will continue to shake his nuclear saber, and Lavrov will continue to mutter about the pernicious failings of the West. Just as predictably, the Russian economy will bottom out, back at its 2010 level. It will stabilize there, beset by capital flight, brain drain, and residual sanctions.

Russia's sense of grievance against the West will grow larger, as will the gap in prosperity between them as Moscow continues to distance itself from its own best interests and remains subordinated to Putin's control.

China will be the ultimate beneficiary, at Russia's expense.

Dr. Frank G. Hoffman serves on the board of advisors at the Foreign Policy Research Institute and is a Distinguished Research Fellow at the National Defense University in Washington, D.C. He has published more than 100 articles in academic and military journals, including the RUSI Journal and Journal of Strategic Studies, as well as several books and numerous book chapters.

"...Zelensky will be the central driver of Ukrainian democratization"

Dr. Lowell Barrington:

It is impossible to say with certainty what a country will look like decades, or even years, in the future.

One can, however, reflect on the factors most likely to affect important long-term outcomes. Ukraine's post-war unity and democracy are outcomes worthy of such reflection.

How united will Ukraine be?

The 2022 invasion shattered Putin's myth of Ukrainians and Russians as one people and made clear his underestimation of Ukraine's growing Ukrainianness.

Prior to the 2022 invasion, Ukraine was a partial, flawed democracy with prevalent corruption...

Recent scholarly works highlight weakened connections to Russia since its seizure of Crimea in 2014 and support of secessionist activities in eastern Ukraine. This occurred alongside a deepening attachment to a citizenship-based civic national identity. If 2014 was a catalyst for diminishing connections to Russia and a strengthening civic Ukrainian national identity, 2022 has propelled these processes forward with great force.

Both trends will aid Ukrainian unity in the years ahead.

How democratic will Ukraine be?

Prior to the 2022 invasion, Ukraine was a partial, flawed democracy with prevalent corruption. Freedom House called Ukraine a "transitional or hybrid regime" in its 2022 analysis.

Ukraine's "democracy percentage" stood at 39.29 out of 100 with a "democracy score" of 3.36 out of 7. By comparison, Czech Republic's percentage was 75.6 and its score 5.54, earning it the "consolidated democracy" label.

The U.S. and Europe can buffer post-war Ukraine against Russian interference and Ukraine's own internal anti-democratic features with a Marshall plan-like effort to rebuild the country. In return, Ukraine will need to show, through a progressive deepening of its democracy, that as an EU member it will look more like the Czech Republic and less like Hungary.

Western efforts will be vital, but Zelensky will be the central driver of Ukrainian democratization. He has said the war is about democracy but has also restricted political parties and independent media as part of the war effort. His broad domestic support and extensive praise (and awards) from the West may strengthen his backing of genuine democracy in Ukraine. They might also encourage an "only I can fix this" brand of populism.

Ukraine's successes on the battlefield this spring do not necessarily imply a successful consolidation of democracy in the longer term.

Dr. Lowell Barrington is an Associate Professor in the Department of Political Science at Marquette University. He specializes in post-communist politics, ethnicity and nationalism, democratization, and political science research methods. He regularly contributes to journals such as Europe-Asia Studies, Post-Soviet Affairs, and Eurasian Geography and Economics.

"Environmental devastation has been one of the methods by which Vladimir Putin sought to destroy Ukrainian sovereignty..."

Dr. Kristina Hook:

Russia’s escalation of war against Ukraine in February 2022 accelerated an ongoing environmental crisis first sparked by their annexation of the Crimean peninsula and invasion into eastern Ukraine in 2014.

My research with Richard Marcantonio has traced multiple environmental risk scenarios linked to Russia’s military activity in Ukraine in 2014 to their broader strategic goals of controlling and degrading Ukrainian sovereignty. With the Ukrainian state and people clear-eyed that their current war with Russia constitutes an existential threat, I expect the Ukrainian military – if appropriately supported by Western military assistance – to successfully liberate territory presently under Russian control in eastern and southern Ukraine.

...large-scale Russian shelling of residential and business districts has released asbestos and particulate matter.

Significant environmental damage

Ukraine is the largest country in Europe, and massive territories across the country are experiencing significant war-related environmental damage.

Short and long-term risks to human health caused by this environmental damage vary according to the dose and length of exposure. Some of these long-term effects will be subtle, for example, as large-scale Russian shelling of residential and business districts has released asbestos and particulate matter. Unaddressed, these cumulative effects will cause healthcare costs to rise and life expectancy to decline, bolstering the case that environmental redress is a first-stage priority for Ukrainian reconstruction aid.

Other environmental risks are more obvious, including the impact of military activity around Ukraine’s 15 nuclear reactors, chemical plants, mines, and other manufacturing facilities.

Effects outside Ukraine

Russia’s indiscriminate bombing, including of the Zaporizhzhia nuclear power plant, heightens the potential for direct or indirect damage (such as to dam infrastructure) to sites with potential consequences for the storage of radioactive waste, such as at the Pridniprovsky chemical plant. These consequences could impact not only citizens in Ukraine’s internationally recognized borders but also in the Russian Federation (especially the Rostov province) and in neighboring countries that share waterways.

Other regional threats include long-term effects of pollution, ecosystem imbalance ramifications, and deforestation and agricultural field harm that will impact millions of consumers of Ukrainian harvests in the Middle East, Africa, and beyond for years. Evidence exists that beyond the current blockade of Ukrainian ports, the Russian military is intensively mining agricultural fields, linking de-mining efforts to both food security and environmental redress priorities.

Long-term risks

Several additional environmental risks raise long-term concerns that Russia’s military invasion will continue to claim or shorten lives for decades to come.

One pressing concern includes contamination caused by the flooding of industrial mines in the Donbas region (Luhansk and Donetsk provinces), where some of the worst artillery and conventional battles now rage.

We have traced the dangers of this flooding since Russia began its invasion in 2014, describing how rising waters can solubilize and transport toxic pollutants – especially heavy metals – into water systems through these industrial areas that have coal mining and Soviet nuclear testing heritage.

The long-term, holistic mitigation of these risks is dependent upon Ukrainian control of the Donbas. Our research illustrates a pattern that the Ukrainian government had relatively robust environmental management and monitoring procedures in place prior to 2014, while the Russian government subsequently exhibited patterns of dissembling and neglect.

Current warfighting makes daily monitoring of these and other environmental risks challenging. But contacts at Ukraine’s Ministry of Environmental Protection and Natural Resources have stated that these mines are presently “unrecoverable” without assistance and the area “uninhabitable... after extreme water pollution,” affecting citizens in Ukraine as well as potentially in Russia.

Many other environmental effects of large-scale urban warfare exist, including reports of damaged chemical waste storage at the Azovstal steel plant in devastated Mariupol with concern of contamination in the Sea of Azov.

In addition to human health and habitat harm, marine biocultures may be threatened, although confirmation is not possible until environmental scientists can access and test samples from the area.

Fires from artillery strikes and other war activities also disrupt modified landscapes and fields, with fire threatening other unique ecosystems in southern Ukraine, including the Kinburn Spit near Mykolaiv.

Overlapping with the neighboring Kherson region, the Black Sea Biosphere Reserve also experienced fires large enough to be detectable from space. Russia’s occupying presence in the Kherson region prevents a full review of damage to natural and bird habitats.

Financial cost

The cost of environmental redress of this war rises daily, although the costs of long-term neglect are higher.

One team of seventy scientists has documented 300 ecological crimes with cost estimates from only several of these incidents at $6.77 billion in damage. Multiple international environmental working groups also exist, and databases with relevant data are housed by Ukraine’s Interior Ministry, Security Services, State Emergency Systems, and some local think tanks.

In the past, my research with Richard Marcantonio has noted Ukrainian bureaucracy coordination challenges and political will obstacles by international partners. For long-term progress, action plans must be created now that incorporate international and Ukrainian anti-corruption ideas for reconstruction aid, as well as Russian Federation reparations and the usage of confiscated assets.

Willful environmental devastation has been one of the methods by which Vladimir Putin sought to destroy Ukrainian sovereignty and undermine a rules-based global order, without regard for the disproportionate harm to the Global South.

A Marshall Plan 2.0, including sustainable and accessible rebuilding that revitalizes Ukraine as a green energy powerhouse, is an important component of future deterrence.

Dr. Kristina Hook is an Assistant Professor of Conflict Management at Kennesaw State University's School of Conflict Management, Peacebuilding, and Development. A specialist in Ukraine and Ukraine-Russia relations, she has research, teaching, and professional experience on topics including genocides and mass atrocities, civilian protection, post-conflict reconstruction, and security challenges such as hybrid warfare and environmental degradation.

"The humanitarian crisis in Ukraine will soon become an unprecedented demographic crisis..."

Dr. Hiroaki Matsuura:

Europe's largest humanitarian crisis in Ukraine will soon become an unprecedented demographic crisis in recent history.

The number of refugees fleeing Ukraine and the death toll are still growing, but these numbers are already large enough to affect the population size and structure of the country.

It is time to establish a system to track the Ukrainian population abroad and support their future return to the country.

In particular, the refugee population is highly concentrated among women and children. They are less likely to return home if they establish their new lives in their destination countries. If most of them do not return like other refugee populations, this will create a significant population loss as well as gender and age imbalance in the population.

Recently, we saw news that a significant number of people have re-entered Ukraine. However, we do not know how many of such returns are temporary stays or permanent returns.

It is essential that the Ukrainian authorities and the international community establish a more systematic collection of data to monitor vital migration flows and stocks in the country and abroad. This is an old problem with new urgency for Ukraine. Ukrainian statistical systems had long failed to capture the temporary and circular nature of its migrant population abroad. It is time to establish such a system to track the Ukrainian population abroad and support their future return to the country.

Dr. Hiroaki Matsuura is Provost and Vice President for Academic Affairs and Professor of Health Economics and Demography at Shoin University in Japan. He's an economist and demographer interested in the intersection between human rights and population health. He's Editor-in-Chief of the Biodemography and Social Biology journal, as well as an editorial board member of journals including the Child Abuse Review, International Journal of Social Welfare, and Sociology of Illness and Health.

Further reading:

- Putin's Strategic Failure by Nigel Gould-Davies in Survival

- Environmental dimensions of conflict and paralyzed responses: the ongoing case of Ukraine and future implications for urban warfare by Kristina Hook and Richard Marcantonio in Small Wars & Insurgencies

- Ukraine 2022: Why and What Next? by Andrzej Makowski in Israel Journal of Foreign Affairs

- Russia’s War against Ukraine: A Trio of Virtual Special Issues by Gwendolyn Sasse in Europe-Asia Studies

- Blogs and podcasts (IISS)

- News and comment (RUSI)

You might also like:

Social justice and sustainability

Find out about the content we publish, commitments we've made, and initiatives we support related to social justice and sustainability:

China

China Africa

Africa