Black resistance through the arts

Leah Kinthaert

The Association for the Study of African American Life and History site illustrates: “African American spirituals, gospel, folk music, hip-hop, and rap have been used to express struggle, hope, and for solidarity in the face of racial oppression…Creatives used poetry, fiction, short stories, plays, films, and television to counter stereotypes and to imagine a present and future with Black people in it.”

In honor of Black History Month, here are some stories and viewpoints on the topic of Black resistance through the arts, utilizing sources from Taylor & Francis books and academic journals, from Art History to Literary Criticism and Cultural Studies.

"...Vogue conjures many things: honed Black and Brown queer and trans bodies, queer space, and communal resistance to hostile worlds...

Survival strategies

On the surface, pop culture may seem like a light, fluffy, distraction, but in actuality it has enormous power for social change, with historical evidence that it can both upset (those who don’t want change) and empower (those who need change). Ubiquitous disco music, which emerged in the U.S. in the late 70s, and has since morphed into genres as varied as house, new wave and hip hop, was once so threatening to a portion of the American population that it spawned an anti-disco moment that culminated in a violent riot of 59,000 rock fans in Chicago.

Voguing, “a vernacular form of dance originating in the Black and Latinx ballroom scene in Harlem, New York” that uses a mix of electronic music, disco, funk, hip-hop, house, and R&B, is an art form that has empowered LGBTQIA+ communities. In the article “Suburban vogue and other queer survival strategies”, Paul Kelaita explains: “Vogue conjures many things: honed Black and Brown queer and trans bodies, queer space, and communal resistance to hostile worlds.” In voguing, a community develops a coded language of dance that's all their own, that provides belonging and a sense of safety. In a place like suburban Sydney, Australia, this art form which originated on the other side of the world, has a power to “instantiate(s) a transnational and cross-spatial imaginary” and be part of a “survival strategy” for a community whose everyday reality is exclusion and violence.

Read more of Suburban vogue and other queer survival strategies from the journal Cultural Studies.

" the Black Power Movement successfully recast the relationship between urban culture, modernity, and African American identity..."

The Black aesthetic

In Black Power Music! Protest Songs, Message Music, and the Black Power Movement, Reiland Rabaka dives into a period of time which, he says, history tends to forget or misinterpret. Rabaka writes: “The Civil Rights Movement is primarily presented as ‘noble and nonviolent’ and the Black Power Movement as ‘vicious and violent’.” Instead, according to Rabaka and African American history experts, the Black Power Movement, from about 1965 to 1975, should be remembered as a time of great sea change where a new mindset of identity pride and self-determination for African Americans was born. Rabaka writes: “as Amy Abugo Ongiri (wrote) in Spectacular Blackness: The Cultural Politics of the Black Power Movement and the Search for the Black Aesthetic…’If the Civil Rights Movement successfully made racism into a moral failing, the Black Power Movement successfully recast the relationship between urban culture, modernity, and African American identity, thereby establishing African American authenticity as defining hip, urban authenticity and cool’” creating “’an astounding array of aesthetic and cultural innovations.” This hipness of a “Black Aesthetic” was positive, and empowering, and as Rabaka explains, it raised the consciousness of Black people who heard it, allowing “countless Black artists to literally decolonize and Blackenize/African American-ize their respective artistic creations.”

Read the concluding chapter of the book, free to access Blackness.Power.Music.

Black is beautiful: a revolutionary gesture

Jo-Ann Morgan, a Professor of African American Studies and Art History recently described her experience teaching about the Black Power era: "As I presented the Black Power era in undergraduate courses two things were quickly apparent. First, the images were compelling. Whereas photographs from the preceding Civil Rights Movement were mainly news reporting, Black Power subjects themselves appeared to be driving a narrative, with photographers complying.

As an example, a well-known photograph of Black Panther Party leader Huey P. Newton was first composed to accompany the party’s Ten-Point Platform in their Black Panther newspaper. His black clothing, his piercing gaze, and the weapons and artifacts assembled around him transmit the Panther stance on self-defense. Even the import store wicker throne upon which he posed lent a veneer of authority. This and other photographs advocating Black Power maintained a consistent theme, a deadly serious commitment to social and political change. A second revelation was how much the Black Power era, then four decades in the rearview mirror, still resonated with young African Americans.”

In her book “The Black Arts Movement and the Black Panther Party in American Visual Culture” Morgan explains how the visual impact of Black Power was just as important to the movement as the messaging. The visual arts had been dominated by a European aesthetic, as Morgan says: “European power brokers had been shaping ideals through visual means for millenniums, making white men masters of the universe, even convincing viewers that Jesus was a blue-eyed blond.” In the late 60s, a “group of writers, activists, and visual artists formed the Organization of Black American Culture (OBAC)” and later groups like AfriCOBRA who worked on such projects as the “Wall of Respect, groundbreaking as a first outdoor mural located within an African American community” and revised “elements of art and principles of design to conform to a more Afrocentric vision, ...refashioned art vocabulary into a new language.”

“The Black Arts Movement and the Black Panther Party in American Visual Culture” can be read free to access here.

"trance as a framework challenges us to take a step into an alternate state of how our consciousness of blackness, as a socio-political and racial identity, continuously moves through and across borders..."

Changing the framework

Scholar Omaris Z. Zamora studies transnational Black Dominican women’s narratives. In her article: “Before Bodak Yellow and Beyond the Post-Soul” she describes the artist Cardi B (one of the most influential female rappers of all time) as “continuously in the process of becoming and self-making” and argues the importance of this examination, as “she is doing Black diaspora feminist theory in the flesh that (scholars) often leave out.” Zamora points out that in order to study Cardi B’s work in the correct context, it’s necessary to actually change the process of not just “what” one is researching but also “how” one is researching. One needs to enter a “trance” space. To explain, a trance is what a performance you’re captivated by might put you in, when you ”feel like the room around (you is) empty and… nothing around (you) matters" - essentially, “the warping of time and space.”

Zamora writes: “trance as a framework challenges us to take a step into an alternate state of how our consciousness of blackness, as a socio-political and racial identity, continuously moves through and across borders. This constant movement alters our historical base where blackness is constrained to a white supremacist lens of nation-building and citizenship”. Zamora’s aim is to: “expand the limits of the post-soul field (an era and aesthetic marked by the post-Civil Rights movement) by taking into account an urban working-class transnational Black diasporic feminism that continues to push the boundaries of blackness.”

Read “Before Bodak Yellow and Beyond the Post-Soul” from the journal The Black Scholar.

"the artist is uniquely placed to confront and expose the political and social purpose of racial bigotry..."

Not waiting for permission

Teresa Hagan is another researcher challenging who and what scholarship should or shouldn’t include. She writes: “Black intellectualism, particularly in the public sphere, tends to be associated with male figures from the academy. This trend risks excluding a broader range of viewpoints and traditions – particularly the contributions of Black women, artists and community organisers whose intellectual praxis has been wrought from experiences outside the academic paradigm”, and argues that activist and filmmaker Ava DuVernay should be included in the paradigm. Quoting DuVernay at the 2017 Sundance Film Festival, where she shared words from Toni Morrison, Hagan agreed with DuVernay that “the artist is uniquely placed to confront and expose the political and social purpose of racial bigotry.”

Hagan argues that Du Vernay’s work, which ranges from historical drama, to feature, to mini-series, “seeks to actively bear witness to lived Black experiences ... acting as counterpoint to a film and television industry which has often been quick to erase or misrepresent them.” Even in Du Vernay’s choice of art form, television over film, “a choice in itself that challenges and resists traditional ideas about the value of low versus high art”, Hagan asserts that Du Vernay chooses to “challenge notions about who gets to be an authoritative intellectual voice – as well as where and by whom that voice can be accessed.”

Read ‘Don’t wait for permission’: Ava DuVernay as a Black female intellectual and political artist from Comparative American Studies An International Journal.

"Beat juggling emerges as a post-modern performance model for historical inquiry and critical perspective..."

Memory as performance, performance as memory

In the Introduction to Volume 49, Issue 3 of The Black Scholar, Black Performance I: Subject and Method, Stephanie Leigh Batiste writes: “As channels toward and markers of memory, performances that engage with blackness place not only specific experiences and circumstances in play with history, but also the meanings of Blackness, the inheritances of Black expressive art making, and the revised futures these come to be.” Batiste goes into more detail on what these “revised futures” entail, citing the work of Gaye Theresa Johnson concerning DJs (who use turntables as instruments): a DJ “encodes and communicates centuries of musical memory, minimizes the distance between different albums and songs, and interpolates a wide range of life experiences into a new beat”. Batiste continues: “Beat juggling emerges as a post-modern performance model for historical inquiry and critical perspective.”

Read the Introduction to Issue 3: Black Performance I: Subject and Method from

The Black Scholar.

"rap music had become a repository for neglected histories..."

“Once I heard it, I remembered”

One of the articles in Black Performance I: Subject and Method written by DJ Lynnée Denise, is about her relationship with the music of Aretha Franklin, who passed away in 2018. The Afterlife of Aretha Franklin's “Rock Steady:” A Case Study in DJ Scholarship begins with an homage, which conveys strongly in the six opening words the incredible significance that Franklin had to her fans: “We knew what time it was.” Denise had been a fan of Franklin as a child, but only after hearing the 1988 song “I’m Housin” by the American hip hop duo EPMD, and finding out much later that samples from Franklin’s song “Rock Steady” were used as part of that song, did she begin to understand the interesting and complex musical heritage spun by Franklin, and other Black women: “For years, I’d listened without knowledge of the fact that DJs and producers were using the recordings of Black women to build this emerging genre called rap music. Through samples, rap music had become a repository for neglected histories, multiple genres of music, and usable ideas.”

Denise continues: “few of us understood how intricately the music of Black women was being used to shape the art of sampling. Eventually, I understood sampling to be a useful device for decoding cultural information; who recorded what, when, why, and where.” Her personal emotional experience was such that, “in some ways, the song felt familiar, as though it was working on me before I was born. Once I heard it, I remembered.” This discovery led DJ Lynnée Denise to coin the term “DJ scholarship” in 2013, in order to: “shift(ing) the public perception of the role of a DJ from being a purveyor of party music to an archivist and information specialist.”

Read The Afterlife of Aretha Franklin's “Rock Steady:” A Case Study in DJ Scholarship from The Black Scholar.

A mural in Detroit, Michigan depicting Aretha Franklin by Desiree Kelly.

A mural in Detroit, Michigan depicting Aretha Franklin by Desiree Kelly.

"we cannot limit our objects of study and modes of analysis to the conventional finished and properly mixed song..."

Method as medium

DJs are not the only popular musical artists who have reinvented the boundaries of sound. In his article “Unmastered: The Queer Black Aesthetics of Unfinished Recordings”, Elliott H. Powell discusses how the very nature of what would be considered a “rough” or “unfinished” recording can be, in itself, an expression or a statement. Powell argues: “for those of us invested in exploring Black popular music’s queer politics, we cannot limit our objects of study and modes of analysis to the conventional finished and properly mixed song.”

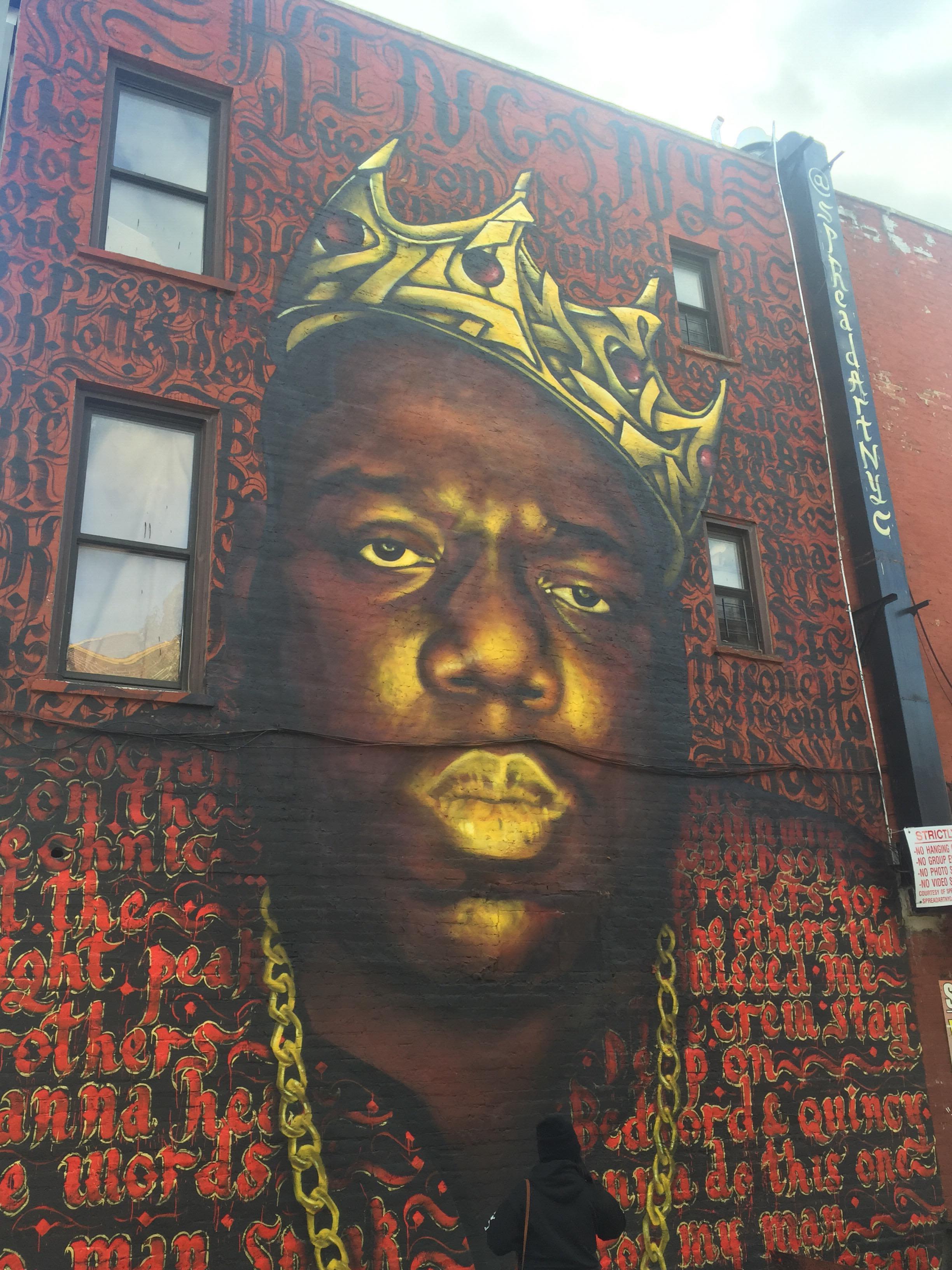

In the music industry, mastering is the final stage of production, when any needed finishing touches to enhance the overall sound and create consistency happen. Powell analyzes “unmastered” work from the artists Prince, Notorious B.I.G., and Lil’ Kim in detail, using them as examples. He asserts: “To be unmastered is to deviate from the normativity of finality and propriety. I contend that it is the unmastered’s resistance to the finished and the fully formed and realized, its challenge to normativity, that gives it its queer potentiality.” Powell continues: “the unmastered holds political possibilities for Black queer communities who are always-already rendered under attack by norms of representation and visibility.”

Read Unmastered: The Queer Black Aesthetics of Unfinished Recordings from The Black Scholar.

A mural of Notorious B.I.G.

A mural of Notorious B.I.G.

"to desire differently, to desire more, to desire better..."

The body politic

Janelle Monáe is a popular singer, rapper, and actor, who has been written about by academics “through the lens of her music, lyrics and sound organization, in relation to the narratives of Afrofuturism, visuality and representation.” In her article, “Gestural Refusals, Embodied Flights: Janelle Monáe’s Vision of Black Queer Futurity”, Aleksandra Szaniawska focuses on Monáe’s body movements: in order to “’read' resistance written within the body itself.”

Szaniawska gives us a little background on Monáe: “Janelle Monáe is a concept artist whose performative projects engender the Afrofuturist vision of Black empowerment. Afrofuturism is a term coined by Mark Dery in his seminal article titled ‘Black to the Future’ (1994), a conversation with Tricia Rose, Greg Tate, and Samuel R. Delany. Drawing from historical memory and ancestral genealogy, Black futurism predates this particular moment, and has functioned as an artistic aesthetic, a framework for cultural theory, and a way to imagine the future through the lens of blackness.” The Wondaland Arts Society which Monáe founded, has an artistic statement which “articulate(s) the revolutionary powers of art in creating a ‘loving’ future as a refuge from present-day inequalities.”

Szaniawska explains: “Monáe’s Afrofuturist performances, her music, film appearances, as well as activism and multiple forms of social engagement, imagine the presence of Black women in spaces that historically have denied their existence.” Beyond this denial, there is creation. “By foregrounding the Black body in motion as a site of endless potentialities, Monáe’s performances engender a gestural vocabulary of Afrofuturism”, says Szaniawska. Inspiring the audience to “step out of the now and in José Esteban Muñoz’s words begin to ‘desire differently, to desire more, to desire better’.” (Note, since this article was published, Monáe has confirmed that they're nonbinary.)

Read “Gestural Refusals, Embodied Flights: Janelle Monáe’s Vision of Black Queer Futurity” from The Black Scholar.

An Afrofuturism style digital illustration of a woman.

An Afrofuturism style digital illustration of a woman.

"dream*hopes... cannot be imprisoned or killed"

dream*hoping

No article on the arts can be complete without a mention of the Harlem Renaissance, a historical, cultural and artistic period that happened around 100 years ago and still inspires new thought today. In this recent article “DREAM*HOPING INTO FUTURES: black women in the harlem renaissance and afrofuturism” Susan Arndt and Omid Soltani write: “The Harlem Renaissance espoused the modernist belief in radical new beginnings and the celebration of (aesthetic) interventions into old certainties, while resisting the “monologism” (Bakhtin) of white Western modernity and modernism.” The authors describe the Harlem Renaissance as a time of “dream*hoping”: “the asterisk marking the fluid entanglement of the two concepts.”

Arndt and Soltani continue: “The early civil rights movement, as represented by such seminal figures as Booker T. Washington, Marcus Garvey, and W.E.B. Du Bois, nourished Black resistance with new ideas and strategies. It is of little wonder then that, to many Blacks, the 1920s felt as a moment in time when the 'dream deferred' would once and for all 'explode' (Hughes, line 11) – a realisation that informed the very spirit of the Harlem Renaissance.” American History, with its discriminatory Jim Crow laws continued to defer those dreams, but the dream*hope remained. Because as Arndt and Soltani explain: “dream*hopes can be silenced, but, unlike humans, they cannot be imprisoned or killed. Bridging individual and collective visions, they can even survive the physical death of the dream*hoper.”

Read “DREAM*HOPING INTO FUTURES: black women in the harlem renaissance and afrofuturism” from the journal Angelaki.

Imagining possible futures through a Black cultural lens

The arts indeed have the ability to empower. But they also have another power, as evidenced in these articles, one that is somewhat intangible; the power to transform, even to transform time, blurring the past and the future into possibilities, or as Arndt and Soltani describe “dream*hopes”. Whether its DJ Lynnée Denise who spoke about the power of music “working on me before I was born” or Monáe’s collective’s Afrofuturism creating a “‘loving’ future as a refuge from present-day inequalities”, experience of the arts as resistance, is experiencing an existence and a place where the seemingly impossible becomes possible.

A futuristic abstract digital painting in the style of Afrofuturism.

A futuristic abstract digital painting in the style of Afrofuturism.

You might also like:

Social justice and sustainability

Find out about the content we publish, commitments we've made, and initiatives we support related to social justice and sustainability:

China

China Africa

Africa