Combatting disinformation

How it spreads and why it's dangerous

The scourge of disinformation, misinformation, and "fake news" has had a massive influence on many recent events.

These include the COVID-19 pandemic, Russia's War in Ukraine, and major political events such as Brexit, the 2016 and 2020 US presidential elections, and the 2014 and 2019 Ukrainian elections.

Now, everyone – even if they're unaware of it – can be part of a disinformation campaign. This could be through engaging with social media bots, sharing manipulated images, or watching "deepfakes" – videos that have been digitally altered through AI (artificial intelligence).

Everyone can also help fight disinformation. The question is, how?

In this article, we're joined by some of the world's leading experts on disinformation, misinformation, and fake news as we look at the factors behind its rise. We also look at disinformation versus misinformation, and why disinformation is dangerous for society.

Importantly, we look at what the authorities, the tech sector, and individuals can do to spot and counter disinformation.

The rise of disinformation and misinformation

It wasn't until 2017 that disinformation and misinformation became a popular topic of study:

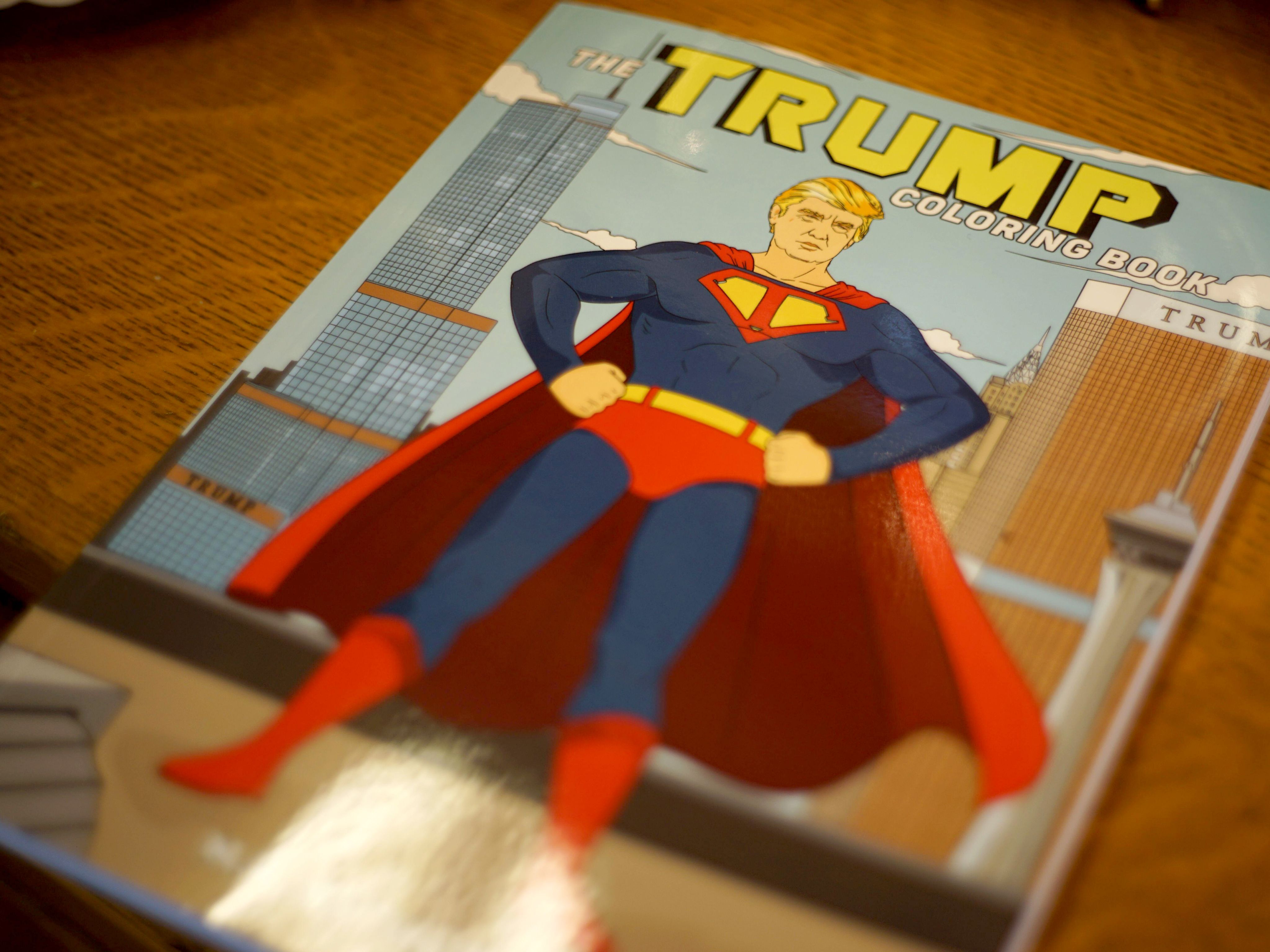

"Two electoral results seem to have brought the concept of disinformation to the fore in the last few years, namely the election of Donald Trump in the US and the Brexit vote in the UK," says Dr. Maria Kyriakidou, Social Media Editor of the Information, Communication & Society journal and Co-Investigator on the Arts and Humanities Research Council (AHRC) project Countering disinformation: enhancing journalistic legitimacy in public service media.

But it's not a new phenomenon.

"There has probably been deception of various kinds in political communication for as long as there has been political communication," says Dr. Regina Lawrence, Editor of the Political Communication journal.

Historical figures such as Louis XIV and Ivan the Terrible used forms of disinformation in military campaigns, while the CIA also used it to influence Congress in the 1980s.

In the 20th century, "its roots go back to the term 'dezinformatsiya,' a strategy used by a division of the Soviet Union's KGB," says Dr. Nicholas Nicoli, co-author of the book Digital Democracy, Social Media and Disinformation.

Disinformation has also been present for a long time in the media.

"The tabloids in the UK have consistently contributed to the spread of disinformation," says Dr. Kyriakidou.

"Migrants and refugees have most often been the victims of such campaigns, although this tendency has mostly been framed in public debates in terms of negative stereotypes, xenophobic, or racist news coverage," she adds.

More recently, "the degree and scope of the coordinated organization behind contemporary disinformation campaigns seems unprecedented, and digital media networks can make it ubiquitous," says Dr. Lawrence.

This is why "the very concept of 'disinformation' is recent" she adds.

"There are more channels, more agents practicing it, more automation in it, and more computational programming from social media worsening it," says Dr. Nicoli.

Dr. Nicoli’s Digital Democracy, Social Media and Disinformation co-author, Professor Petros Iosifidis, agrees that the political landscape has also influenced the increased spread of disinformation.

"Fake news is associated with the rise of social media as well as the popularity of populist and nationalist – especially right-wing – political parties," he says.

"In tandem with the rise of digital technologies, there has been an increase in social and political polarization," adds Dr. Eileen Culloty, co-author of the book Disinformation and Manipulation in Digital Media.

Disinformation vs misinformation

Disinformation, misinformation, and fake news are closely related. But there are some key differences.

"The distinction between misinformation and disinformation is about intention," says Dr. Culloty.

"Misinformation is false information that is shared without an intention to mislead. For example, there is an error or a misunderstanding."

"In contrast, disinformation is false information that is shared on purpose with the intention to mislead."

The distinction between misinformation and disinformation is about intention

Disinformation vs fake news

What about "fake news"?

"Fake news is a specific type or format of disinformation: false information that is designed to look like legitimate news," says Dr. Culloty.

"With fake news, the intention to deceive, to lie, is high," adds journalist-turned-researcher Dr. Pedro Jerónimo. Dr. Jerónimo leads MediaTrust.Lab, a fact-checking research project focused on local media and small communities.

"For example, using real content, such as photographs or posts and comments on social networks. And using the same type of structure as a news item – title, lead, contextualization – there is a clear objective to deceive."

With fake news, the intention to deceive, to lie, is high

Blurred meanings

"Of course, it is not always easy to draw a line between disinformation and misinformation," says Dr. Kyriakidou.

"Once disinformation finds a public forum it can then be shared and spread without the intention to deceive, by people that actually believe in it."

Dr. Lawrence places less importance on the differences between disinformation, misinformation, and fake news:

"I am less concerned about making these distinctions than with understanding the overall phenomenon of poor quality and deceptive information that now seems to flood the media ecosystem," she says.

Once disinformation finds a public forum it can then be shared and spread without the intention to deceive, by people that actually believe in it

Disinformation vs propaganda

Disinformation is also closely related to propaganda.

In The Routledge Companion to Media Disinformation and Populism, Professor Howard Tumber and Professor Silvio Waisbord say disinformation and propaganda both "refer to spreading information and ideas linked to the exercise of power."

The distinction, they say, is that while disinformation is deliberate deception through fabrications, propaganda can also involve spreading information that may not always be false.

Propaganda also involves leaving out inconvenient facts or being selective about what information is shared.

Propaganda can also involve spreading information that may not always be false

Who spreads disinformation?

"The very model of contemporary disinformation depends on three kinds of actors," says Dr. Lawrence.

One: "Those who deliberately create false/misleading information and images meant to mislead citizens and disrupt democratic society and deliberation."

Two: "Those who pass that information along to their own social networks – because they believe it, or they just find it 'interesting.' Or because others in their networks are also sharing it so they think they 'should.'"

Three: "Those who amplify disinformation in the very process of reporting on it and trying to reveal its falsehoods (i.e., journalists)."

Sevens types of perpetrator/actor

In their open access book Social Media and Hate, Professor Shakuntala Banaji and Dr. Ram Bhat investigated the intersections between disinformation, misinformation, and social and media hate.

They found that the following actors produce and pass on disinformation:

1. Organized state-linked groups/actors (paid and unpaid)

These usually work for right-wing or far-right governments with socially and economically authoritarian goals. In countries with weak liberal or leftist governments, they may work for the main right-wing opposition party.

2. Organized non-state groups/actors (paid and unpaid)

These usually work on behalf of (or think they work on behalf of) the government or ruling party, or a racial or religious supremacist ideology. In countries with weak liberal or leftist governments, they may work for the main right-wing opposition party.

3. Unorganized non-state actors

These are united by prejudices or by presumed caste/religious/ethical or racial identity. They're usually digitally literate and act independently.

4. Opportunist grifters

These troll/spread misinformation to increase their fame, following, or finances. They're usually high-profile people or once held left/liberal values and are now publicly performing their right-wing allegiance for economic or political gain.

5. Disruptive libertarians

These aim to disrupt, destabilize, and unsettle political consensus on specific issues (such as vaccines or medical advice) by methods such as trolling and flaming (posting insults). They may mock particular individuals who support causes that they oppose.

6. Digital stalkers

These target individual social media handles for ideological or personal reasons, or through a sense of spurned affection/loyalty which may spill over into violence.

7. Intermittent trolls

These are malicious users, inexperienced users. They get involved because of peer pressure or out of fear of being targeted themselves.

From Social Media and Hate, pp. 22–23 © Shakuntala Banaji and Ram Bhat – used with permission.

The dangers of disinformation

Disinformation is damaging because it causes people to make uninformed decisions that aren't in their interests or the interests of society.

"It encourages people to refuse life-saving vaccines, to dismiss scientific warnings about the need to act on climate change, to elect leaders who lie, and to scapegoat certain groups," says Dr. Culloty.

"We might vote for an outcome under false pretenses; we might decide on a health issue based on wrong information," adds Dr. Nicoli.

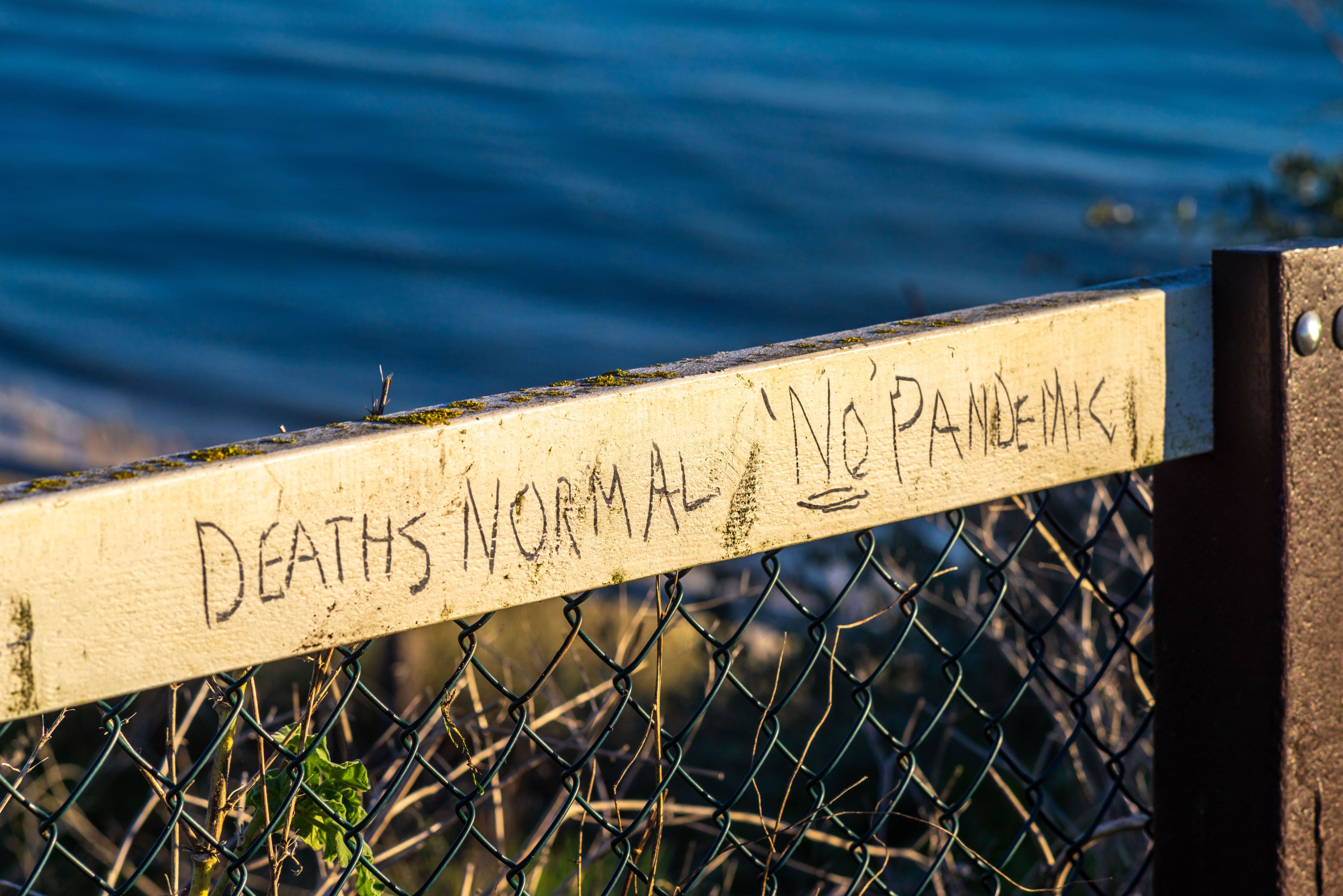

"A good example of this is the pandemic caused by COVID-19 and all the rumors and conspiracy theories, which caused social alarm and helped to spread the virus, increasing the number of cases," says Dr. Jerónimo.

Disinformation also causes people to lose trust in the democratic process.

"Ultimately, disinformation is seen as a major threat to democratic politics," says Dr. Kyriakidou.

"Citizens get deliberately deceptive news so rational, political discussion cannot be conducted in the online public sphere," adds Professor Iosifidis.

"If we know disinformation exists and is not controlled, we will lose trust in those systems which are in place to protect the public interest and the democratic process," says Dr. Nicoli.

Disinformation is seen as a major threat to democratic politics

How social media companies, regulators, and policymakers can counter disinformation

We've seen that social media and technology are mainly responsible for the spread of disinformation. So, what is the technology sector doing to combat it?

"Not enough!" according to Dr. Lawrence.

"And frankly they have little incentive to self-regulate effectively."

Dr. Culloty adds: "There are potentially big gaps between what platforms say they are doing and what they actually are doing.

"For example, it's easy for platforms to report that they are countering disinformation by labeling content, but if they don't run experiments to test the effectiveness of those labels or provide basic information about who sees the labels and what do people do afterwards, it's just a gesture."

Dr. Nicoli highlights that social media companies are using AI systems to detect disinformation, hiring fact checkers, and creating oversight boards that decide how content is moderated on their platforms.

"It seems though, that these are not enough," he says.

Professor Iosifidis concurs: "Self-regulation may not be sufficient, so formal state regulation may be needed."

"Various regulatory, educational, and technological interventions have been proposed to limit the actions of bad actors, to make social media platforms more transparent, and to support and build resilience among audiences. Those actions put emphasis on disinformation content and how it is shared and received," says Dr. Culloty.

"However, if disinformation is understood as a more systemic issue connected to democratic legitimacy, declining trust, and the deepening of social divisions, that would suggest more radical efforts are needed to rethink democratic participation, education, and technological governance."

"One of the policy proposals that's most interesting is to either incentivize or force the platforms to move away from algorithmically driven recommendation systems," says Dr. Lawrence.

There are potentially big gaps between what platforms say they are doing and what they actually are doing

A strong and free media sector

"What is necessary in the fight against disinformation is a strong, free, and independent media sector, which requires government funding and investment," says Dr. Kyriakidou.

"The privatization of Channel 4 and threats to axe the BBC license fee in the UK are steps towards the opposite direction."

It's important too that regulation doesn't suppress fundamental rights.

"This is a discussion as it could easily slide into the realm of freedom of expression," warns Dr. Jerónimo.

This could easily slide into the realm of freedom of expression

Media literacy and education

Another way governments and policymakers can intervene is through education.

"Media and news literacy programs can help," says Dr. Nicoli.

Professor Iosifidis agrees: "I think news literacy is key to combat disinformation."

Fighting disinformation through increased media literacy is already a priority in countries such as Portugal:

"Since the last congress of Portuguese journalists in 2017, the Union of Journalists has been working with the Ministry of Education, with the aim of training primary and secondary school teachers," says Dr. Jerónimo.

News literacy is key to combat disinformation

Four strategies for combatting digital disinformation

In their 2020 article, "Strategies for Combating the Scourge of Digital Disinformation," Randolph H. Pherson, Penelope Mort Ranta, and Casey Cannon proposed radical strategies for combatting digital disinformation and highlighted the advantages and disadvantages of each approach.

1. Pinocchio Warnings

Government legislation could require major commercial search engines and social media platforms to display warning notices when a user views a questionable website or post. Service providers would rely on AI algorithms and an army of independent fact-checkers to identify digital disinformation.

2. The Alt-Net

Governments could create an alternative internet that bans users from posting disinformation. Publishers would be certified to gain access and would agree to abide by a set of universal standards for exchanging information and insights.

3. Rigid Gateways

Key providers of online services could band together to establish strict screening protocols to ensure only acceptable content will be posted on their platforms or websites.

4. The Trust-Cloud

Key providers of online services could create a "safe space" or "trust cloud" on the Internet that houses only validated information from trusted sources.

How individuals can spot and fight disinformation

Dealing with disinformation is clearly a challenge for the tech sector, regulators, and policymakers. Fortunately, individuals can help in the fight too.

Dr. Lawrence says we need to be open to the idea that we might be receiving and accepting disinformation.

We then need to practice "good information hygiene," says Dr. Culloty.

"Take a moment to stop, think, and check where the information is coming from," she says.

"Ask, 'Is this real?' or 'is it credible?'

"Also think about the motives behind the content: is it trying to promote or sell something?

"Check the source by looking it up to see who created it. Cross-check claims with reliable sources to compare what they are saying.

"If in doubt, do not hit like or share."

"Individuals shouldn't solely rely on commercial and subscription-based media for reliable and accurate news," adds Professor Iosifidis.

"Access various sources for news and do not rely on one only," he says.

Suspect, Search, Share

Dr. Jerónimo recommends following the "triple S" framework:

"Suspect. Search. Share."

Suspect

"Always question the content you come across, even if it comes from people you trust a lot – including journalists!

"For a recent study, Professor Marta Sánchez Esparza and I interviewed local journalists from Portugal and Spain. We found they are almost 'blind’ when it comes to official sources and may not fact-check the ones they trust a lot."

Search

"Then search for more information about what you saw."

Share

"Finally, if you come to the conclusion that something is true, share it."

Dr. Jerónimo also recommends sharing disinformation, so long as you add context.

"Deconstruct the original content and enrich it with sources that help others to understand that the original content is not correct."

Helping friends and family

We can also help halt the spread of disinformation by helping protect friends and family from it, says Dr. Lawrence:

"We need new ways of talking to the people in our lives that we care about in ways that might help them be less susceptible to disinformation."

Further reading:

Journal articles

- "We Aren’t Fake News": The Information Politics of the 2018 #FreePress Editorial Campaign by Regina G. Lawrence and Young Eun Moon in Journalism Studies

- How Disinformation Reshaped the Relationship between Journalism and Media and Information Literacy (MIL): Old and New Perspectives Revisited by Divina Frau-Meigs in Digital Journalism

- "Who is gullible to political disinformation?" Predicting susceptibility of university students to fake news by Rex P. Bringulaa et al. in Journal of Information Technology & Politics

- Disinformation as Political Communication by Dean Freelon and Chris Wells in Political Communication

- Why Media Systems Matter: A Fact-Checking Study of UK Television News during the Coronavirus Pandemic by Stephen Cushion et al. in Digital Journalism

Books

- Digital Democracy, Social Media and Disinformation by Petros Iosifidis and Nicholas Nicoli

- Social Media and Hate by Shakuntala Banaji and Dr. Ram Bhat (read this book for free)

- Disinformation and Manipulation in Digital Media by Eileen Culloty and Jane Suiter

You might also like:

Social justice and sustainability

Find out about the content we publish, commitments we've made, and initiatives we support related to social justice and sustainability:

China

China Africa

Africa