June Purvis and the herstory of Women's History Review

By Leah Kinthaert

On the heels of the women's movement in the 1970s, Women’s Studies was born, to address and research topics such as race, class, gender, and sexuality, in departments as varied as history, sociology, literature, politics, and psychology, with the goal of changing the position of women in the world.

2022 marked the 50th anniversary of two of the first scholarly journals in Women's Studies, our own Women's Studies, and Feminist Studies, which were both founded in 1972. 1972 was also the year that the Women’s Studies Newsletter, which is now WSQ: Women’s Studies Quarterly, was founded. Through the 80s and 90s, "academic interest in women’s, gender, sexuality, and queer studies diversified" and there are now more than 50 women's studies journals globally.

Taylor & Francis imprints Routledge and (before 2005) Carfax were some of the original movers and shakers in gender studies, helping to bring together communities through their books and journals program.

Taylor & Francis' Women's History Review is one of only four academic journals devoted to women's history, along with Clio. Femmes, Genre, Histoire; Journal of Women's History; and Gender and History.

Since this year's theme for Women's History Month is "Women who tell our stories," I wanted to make sure we were telling the very important story of the origins and founding of Women's History Review. A Google search didn't bring up very much on the backstory of this journal, and that was something that needed to be remedied. So I contacted June Purvis, Professor of Women’s and Gender History (Emerita), University of Portsmouth, Founding and Managing Editor of Women’s History Review, and Editor for a Routledge Women’s and Gender History Book Series, and was delighted when she got back to me.

I sat down with June Purvis, virtually, and asked her to take me back to 1992, the year Women's History Review was founded, and tell the story of why it was started, and why its existence is just as important today, 30 years later.

Know your history

One of the most powerful tools for social change is the consciousness-raising that comes from unearthing stories, facts, and artifacts from the past. Many groups that enjoy rights now, for example, U.K. women who currently have the right to vote, enjoy these rights because women fought very hard for them. While the 1910 postcard pictured, showing the "dangers" of women voting, may be downright silly, the humor is thinly veiled, dehumanizing ridicule of women. This artifact is proof that a time existed when it was quite OK for women in that part of the world to be dismissed and disenfranchised.

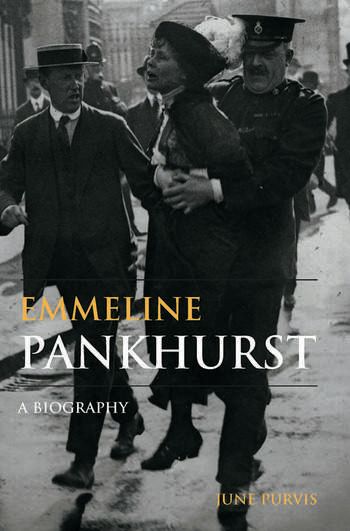

While for many of us, the term suffragette might bring to mind elegant 19th-century ladies in hats, wearing lovely attire, many of the harsh realities of women who fought for the right to vote, for example, Emmeline and Christabel Pankhurst, both of whom June Purvis has researched, were far from garden party picturesque. Lizzie Pook explains: "Less is known about how horrifically these (suffragettes) campaigners were treated and how much they sacrificed for the cause – losing dignity, jobs, marriages, children, even lives... suffragettes endured imprisonment, hunger strikes, and force-feeding. Many carried the scars, physical and mental, for the rest of their lives. Some died."

While the days of fighting for women's suffrage in the U.K., U.S., and elsewhere, were fraught with violence and great risk, we only have the ability to know those stories because women like June Purvis have been telling them. And telling those stories for the first time was not without challenges. Purvis recounts the somewhat rocky road that led to the earliest attempts at legitimizing something called "Women's History."

I remember reading Sheila Rowbotham's 1973 book "Hidden from History" with great joy

June Purvis takes us back to her university days, with vivid detail, when I ask her why she founded Women's History Review: "My first degree was in Sociology and my Ph.D., undertaken at the Open University, was into the education of working-class women in nineteenth-century England. Keen to read about the women I was researching, I found few secondary publications on the topic. Mainstream history was malestream, very much concerned with men’s activities in wars, parliament, politics, business, and administration. When women were mentioned it was often in regard to their relation to men, as wives, sisters, daughters, and mistresses. Although the Second Wave of the women’s movement in Britain, the USA, and Western Europe had given rise to some publications in women’s history, it was still very much marginalized and, if taught at all, taught by those paid precarious salaries outside universities."

Purvis continues: "Sheila Rowbotham’s 1973 book, Hidden From History: 300 Years of Women’s Oppression and the Fight Against It, is usually regarded as the ‘taking off’ point for women’s history in Britain and I can remember reading it with great joy. Sheila and other socialist feminists, such as Anna Davin, Sally Alexander, Barbara Taylor, and Jill Liddington, were all influential in shaping the 'new' women's history that was evolving."

When women were mentioned it was often in regard to their relation to men, as wives, sisters, daughters, and mistresses

Purvis describes how, in the 80s and early 90s, a completely new approach to examining history was born: "The dominance of the socialist feminist voice within women’s history at this time led to a forging of strong links with socialist and labor history, and the way that women’s struggle against oppression was allied with the class struggle against capitalist exploitation. Since gender and class divisions were closely intertwined, there was an emphasis on writing a ‘history from below,' a history of working-class women."

"Having researched working-class women in the nineteenth century, I had much sympathy with this approach. But I wanted a journal that included a wider variety of feminist perspectives and a wider range of women. In particular, I had been reading the historical work of a number of radical feminist writers who were not located within the discipline of History but in Women’s Studies."

'Patriarchy'... was the source of women’s oppression, rather than capitalism

I asked Purvis if there were any other journals that she found to be influential at the time and if Women's History Review was indeed one of the first. She explained what motivated her to create a new forum: "There were other influential journals in the field at the time but I found them lacking in what I wanted, which was mainly British women’s history. The Journal of Women’s History had been founded in the USA in 1989 but it published mainly articles on North American women’s history. That same year, Gender & History was founded too, with the late Leonore Davidoff, who held a chair at the University of Essex, here in the U.K., as its Editor. It was organized by an Anglo-American collective and, as its title says, focusing on gender, by addressing men and masculinity, as well as women and femininity."

I feared that putting 'gender' rather than 'women' in the title would again lead to women’s history being marginalized...

"I was not particularly happy with the approach outlined by Gender & History. Although 'women' and 'gender' are closely intertwined, I feared that putting 'gender' rather than 'women' in the title would again lead to women's history being marginalized. Some years earlier I had founded the journal Gender and Education which was published by Carfax, owned by Roger Osborn-King. So I contacted Roger and asked him if he would be interested in a women's history journal. He was! I gave up my Editorship of Gender and Education, which attracted few historical articles anyway, and set about establishing Women’s History Review. To this day I am very grateful to Roger for the faith he had in me, and for his enduring support."

Purvis continues: "Excitedly, I wrote to Leonore Davidoff to tell her about my plans, asking her to wish me luck and pointing out that I hoped our respective journals would not be competitors but complement each other. Leonore was not enthusiastic and concerned about what she called 'the practicalities.' In particular, she stated in her letter to me that both the Journal of Women’s History and Gender & History had not had an easy time in getting subscriptions, especially from libraries, and that I had not outlined how my proposal would differ from Gender & History."

"But I was determined to press ahead with founding an academic, peer-reviewed women’s history journal and contacted a number of scholars in the field, asking for their help to form an international editorial board and to encourage people to send us manuscripts. Philippa Levine, who was then at the University of Southern California, became our deputy editor, and June Hannam, at what was then Bristol Polytechnic (later University of the West of England), our Book Reviews Editor. The new journal could not have got off the ground without the support of these two people and so many others, too many to mention. So I would say that I was among the first to found a women’s history journal."

Feminists (are) like lemmings

I was curious to know if there were any roadblocks to founding a new journal, with a new type of scholarship, and Purvis had several anecdotes to provide. Shaking things up in the academy had its share of detractors.

Purvis elaborated: "Founding a new journal is really a leap of faith! I was lucky in that many people were keen on the idea. There was an active Women’s History Network in the U.K., which held annual conferences where many excellent papers were given which were looking for a home. And, of prime importance, was the fact that many of us teaching in higher education in the UK needed articles on women’s history in order to help get the subject into the curriculum."

If I knew (you) were going to talk about the patriarchy, I would not have let (you) give the paper

"Some male scholars, however, were very skeptical about it all, arguing that a journal titled Women’s History Review was too narrow and that there were not enough primary sources for the journal to be a success. I can remember one distinguished scholar (not a historian) telling me that feminists, like myself, were like lemmings, all focusing on women and running together ready to jump over a cliff! And on another occasion, when I mentioned the word patriarchy while giving a paper on the education of working-class women in nineteenth-century England, I was firmly scolded after the event by the male chair of the session who said that if he had known I was going to talk about patriarchy, he would not have let me give the paper! The irony of the situation he did not see."

While the late 80s and early 90s were a renaissance of feminist thought, there was also a backlash in the 10 to 20 years following that period. Many women in the U.S., for example, even found it necessary to precede their opinions on women with "I'm not a feminist, but". Now feminism has become more acceptable in the mainstream of many cultures, fueled by the #MeToo movement.

I asked June Purvis how the journal has changed since its launch, and what she thinks the future may hold. Purvis' words' echoed the above sentiments about the fickleness of society's acceptance of feminism.

As the American historian Judith Bennett has remarked, 'patriarchy' was readily talked about by historians of women in the 1970s and 1980s but in the twenty-first century is barely whispered

"Over the last few decades, Women’s History Review has become 'less' feminist in a hard-hitting sense in that it is less concerned with the sexual dynamics of power between women and men. As the American historian Judith Bennett has remarked, 'patriarchy' was readily talked about by historians of women in the 1970s and 1980s but in the twenty-first century is barely whispered. However, I would argue that even making a women’s centered women’s history visible is feminist and has helped the massive growth of the field."

"The journal’s coverage, compared to the early 1990s, is now much more international, featuring the stories of women from all over the globe. Further, it is important to remember that women's history is no longer written just by historians but includes scholars in film and media, literary studies, cultural studies, human geography, colonial, and postcolonial history – and the journal reflects this."

"Women’s History Review has two main formats – the usual academic article of up to about 10,000 words and much shorter 'Viewpoints,' which usually reflect the experiences and views of the author or argue a particular case. Our Viewpoints have increased in number and vary enormously. They have included the university lecturer Sarah Crook writing about the experiences of academic mothers under COVID, filmmaker Sarah Gavron talking about the making of the film Suffragette, as well as recollections by a non-academic author Angele McPherson, about her fascist grandmother."

There can be no going back to pre-1970s days. All the indications are that women’s history is here to stay.

Purvis didn't want to try and predict the future, but offered assurances that the groundwork she and many other scholars have laid in women's studies will continue to flourish.

"It is difficult to predict the future but I hope Women’s History Review continues to grow in strength and coverage. Throughout the world there are a number of active local, national, and international women’s history societies, including here in the UK, and women’s/gender history is now part of the curriculum in many universities. Stories about women’s lives in the past are also now part of popular culture in Western societies and regularly shown on TV screens. This bodes well for Women’s History Review."

"On the other hand, the post-COVID recession that has hit many societies worldwide has created a time of austerity where the arts and humanities are often less valued than vocational courses. But there can be no going back to the pre-1970s days. All the indications are that women’s history is here to stay and that it will continue to be reconceptualized and reformulated as it is communicated in more diverse forms than we could ever have imagined in the 1970s."

This U.K. postcard from 1910 reminds us how attitudes toward women have changed radically in many places.

This U.K. postcard from 1910 reminds us how attitudes toward women have changed radically in many places.

A recent cover of Women's History Review

A recent cover of Women's History Review

Emmeline Pankhurst: A Biography, by June Purvis, 2002

Emmeline Pankhurst: A Biography, by June Purvis, 2002

Christabel Pankhurst: A Biography, by June Purvis, 2018

Christabel Pankhurst: A Biography, by June Purvis, 2018

The British Women’s Suffrage Campaign: National and International Perspectives, by June Purvis, (Editor), and June Hannam, (Editor)

The British Women’s Suffrage Campaign: National and International Perspectives, by June Purvis, (Editor), and June Hannam, (Editor)

You might also like:

Insights and blogs

- Women healers: from ancient shamans to 21st century doulas

- Diversity in academic publishing: How can publishers help repair the 'leaky pipeline'?

- Inspiring women in AI

- Diversity in Peer Review

- Women in Publishing Employee Resource Group at Taylor & Francis

- Getting more girls in STEM

- What is social justice?

Social justice and sustainability

Find out about the content we publish, commitments we've made, and initiatives we support related to social justice and sustainability:

China

China Africa

Africa